Actress Files: Simone Signoret

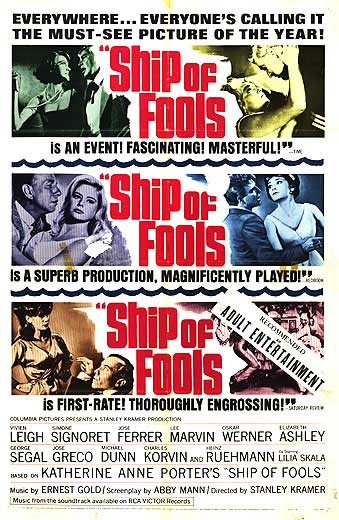

Simone Signoret, Ship of Fools

Simone Signoret, Ship of Fools★ ★ ★ ★ ★

(lost the 1965 Best Actress Oscar to Julie Christie for Darling)

Why I Waited: Has anyone ever hustled to see Ship of Fools? 150 minutes of Stanley Kramer mixing and matching thinly archetypal characters with all of his typical subtlety?

The Performance: Voters handed eight nominations and two wins to Ship of Fools in 1965, so clearly they found something to like. Those dual wins, for Ernest Laszlo's sleek black & white photography and for Robert Clatworthy and Joseph Kish's luxe but elegant design of the cruise ship, even pass muster by Oscar's standards, which means having to accept the fact that, despite the splendid Best Director nod for Hiroshi Teshigahara's Woman in the Dunes, it's too much to ask for that film's indelible visuals to snag the trophies they merited. But Ship of Fools, despite the famous Kramer imprimatur, arrived in port as one of those Best Picture contenders with no corresponding nod in Best Director, implying attenuated enthusiasm among the more sophisticated nominators. The actors were more generous with their balloting. Given their proclivities, I suppose there's no way they could overlook the twee stylings of 3'11" Michael Dunn, breaking the fourth wall with discomfiting, barker-ish merriment at the beginning of the movie—"My name is Karl Glocken," he avers directly to the camera, "and this is a ship of fools!"—and venturing a hollow, ironical knowingness in a bookending coda. Dunn predictably placed and justifiably lost the Best Supporting Actor Oscar, but setting him aside, in the leading categories, the Acting Branch sent a strong message that for all the interlocking vignettes linking Vivien Leigh's caustic spinster to Lee Marvin's bellyaching bully to José Ferrer's hambone Nazi to Heinz Rühmann's optimistic Jewish salesman to Elizabeth Ashley and George Segal's amorous young bickerers, etc., etc., the rueful romance between Simone Signoret's condemned countess and Oskar Werner's stoical shipboard doctor was the obvious diamond in this pail of ice.

As a framing aside, I found Elizabeth Ashley lively and naughty, confiding about Segal's handsome, self-pitying boor that "David's an artist, a wonderful one... He's all caught up with social consciousness right now, but he'll get over it." Would that Kramer had ever done the same, though I'm impressed he would tolerate a line that inevitably sounds like a crack on his own sensibilities. The film moves briskly enough and there are some pert moments, as though enough of the actors see how badly Ship of Fools could use some humor and verve. When things did feel dull, I thought about poor Irwin Allen, who must have labored to survive this movie at some point in his career and thought, If only they'd collide with a tidal wave or an iceberg! Ship of Fools has the starrily-cast but perfunctory patchiness of a disaster movie without the disaster. Then again, for many viewers, all of these earnest declamations and ham-handed, heavy-hearted ironies are disastrous enough, thank you very much. My point is, though, that the actors were onto something in singling out Signoret and Werner for real praise. It's one thing to sidestep the crude literalisms of the script with tart bitchiness, as Vivien Leigh does. "Maybe you were too busy lynching Negroes to take time out for the Jews!" she slings at an American who fumes hypocritically about Ferrer's blunt anti-Semitism. Leigh must have figured this cruise-ship was the closest she'd ever get to doing Tallulah in Lifeboat, and why deny her her fun?

Signoret and Werner, though, opt for a more difficult course than leavening solemnity with tart flippancy. They find a way to play Ship of Fools in a key barely distinguishable, if at all, from the doleful one in which it's been written, but they find real aches and nerve-endings where one would forgive them for finding nothing but contrivances and canned tears. Signoret has been sentenced to die for aiding working-class insurrections in Cuba, offering shelter to revolutionary leaders on her colonial estate. When the ship picks her up from the arresting authorities, she is escorted up a gangplank after filing through a mob of cheering Cuban peasants. Their joy was so pronounced and her own demeanor so sober that, while my brain may already have been narcotized by other dimensions of Ship of Fools, I initially mistook her as someone that the Cubans were thrilled to behold in handcuffs, taking her public lumps. I wouldn't necessarily confide an error like that except that it gives you an idea how austere Signoret is in refusing to play the sanctified martyr. She wears her righteousness and her fate with the neutral formality of a guilty convict of the higher caste, determined not to disclose her emotions or give her arraigners any pleasure.

Signoret and Werner, though, opt for a more difficult course than leavening solemnity with tart flippancy. They find a way to play Ship of Fools in a key barely distinguishable, if at all, from the doleful one in which it's been written, but they find real aches and nerve-endings where one would forgive them for finding nothing but contrivances and canned tears. Signoret has been sentenced to die for aiding working-class insurrections in Cuba, offering shelter to revolutionary leaders on her colonial estate. When the ship picks her up from the arresting authorities, she is escorted up a gangplank after filing through a mob of cheering Cuban peasants. Their joy was so pronounced and her own demeanor so sober that, while my brain may already have been narcotized by other dimensions of Ship of Fools, I initially mistook her as someone that the Cubans were thrilled to behold in handcuffs, taking her public lumps. I wouldn't necessarily confide an error like that except that it gives you an idea how austere Signoret is in refusing to play the sanctified martyr. She wears her righteousness and her fate with the neutral formality of a guilty convict of the higher caste, determined not to disclose her emotions or give her arraigners any pleasure. That's an extremely refreshing approach to screen heroism, particularly in a vehicle this earmarked for liberal self-recognition, even maudlin complacency that Now We Know Better. I probably run the risk in lots of these profiles of crediting entirely to the actress what is in fact a blend of the director's, the writer's and the performer's inspirations; since Kramer can be a difficult filmmaker to praise, I should admit that Signoret would never get away with the implacable humility of this performance if Kramer weren't allowing or even encouraging that take on the character. Yet there is something truly wise and rigorously un-narcissistic in the ways Signoret handles these dimensions of the character, which feel personal to her, exemplary of her acting style and her politics. (Just like yesterday, we're dealing here with a nationally iconic performer who was equally lionized for her outspoken efforts against dominant ideology.) After gently but firmly rebuffing that quandrant of the audience who might desire to behold a damp-eyed Joan of Arc or an indignant firebrand shaking her own chains, Signoret maintains her tight leash on any form of sentimental self-congratulation, even as her character divulges the motives and details of her radical sympathies to Werner's admiring doctor. In a key monologue, she recalls visiting a Cuban worker on the estate that fed her own fortune. "'Pardon me for my house, pardon me for the way it looks, pardon me for ...everything. Most of this place is a garbage dump and I'm just a piece of garbage,'" she quotes or maybe paraphrases the woman as saying, but Signoret doesn't pour unneeded bathos or pregnant pauses into the line. She preserves a downcast but determinedly cool, candid monotone, revealing the Countess to be a kind of chagrined, familiar journalist of the facts of poverty, not a sensationalizing vendor of the exploitable details of suffering. She exudes a heavy though not an exhausted fatigue in the face of the sheer pervasiveness of inequality—matter-of-factly plumping her pillows and angling away from the camera's gaze or from Werner's as she describes how she secreted key agitators in her private chapel, and providing them with arms.

You won't know if you haven't seen the movie, but simultaneously to all this, Signoret is powerfully, poignantly attracted to Werner's blond, clear-eyed doctor, and she has flirted with him repeatedly in advance of this scene—with dignity but still very openly. Obviously mindful of her death sentence, and eventually informed that he, in his own way, faces one as well, Signoret's middle-aged Countess doesn't seem especially embarrassed at trying to lure the doctor into a short-lived, middle-aged romance, even after he admits to being married, albeit dispassionately. Concisely signaling with her eyes the sad, self-conscious ridiculousness of her situation, the condamnée à mort seeking eleventh-hour succor, the handsome but (let's admit it) froggy-looking woman who can't help wanting to kiss this Aryan prince, Signoret's Countess is more than willing to play some well-worn roles: the woman who's seen it all, the addict in need of saving, the lonely diva imploring a lover's embrace with no strings. She says things that one of Tennessee Williams' fading, deluded flowers would say: "My darling, Love, for once let's kiss in broad daylight." Signoret is already smart casting, since there's a certain armature of reserve, lucidity, and integrity she seems incapable of relinquishing even in a dubious part like this one. Still, her avoidance of mawkishness is obviously the product not just of who and how she is, but of deliberate choices and vigilant self-monitoring. Humorous interludes help, as when she pretends to read Lady Chatterley's Lover to Werner as a sleep aid, only to reveal that she's making it all up, and the volume she's actually holding is a textbook called Natural Resistance and Clinical Medicine. But even amidst this campaign to endear herself to a handsome, only somewhat reluctant admirer, who even seems to find her political principles a major turn-on ("I haven't met many people in my life who have committed themselves to anything," he confesses), she still won't short-change a serious gesture she made in the name of social justice as a manipulable tool to entice an escort. I did wonder, though, through the retrospective lens of the Countess's overt yearning for human connection, whether her self-endangering commitment to the revolutionaries was at all motivated—not instead but maybe alongside the unequivocal rightness of the cause—by its promise of camaraderie. Was her valiant collusion one more way not to be so devastatingly lonely?

Signoret's performance raises interesting conundrums for this star-rating system, because I found it to be an impeccably judged approach to a role that scores of other actresses would have fumbled, lacking the tonal control or the palpable moral intelligence through which Signoret movingly humanizes and redeems it. Even her final "Bye" to Werner, at the end of a highly-charged scene, is piquantly quick and quiet. That said, the limitations of the role are such that it essentially prohibits a truly great performance. I can't imagine the wizardry that would be required to divest it of all traces of cliché, which Signoret hasn't done, and her admirable choice for deft, cool underplaying admittedly has the effect of keeping her within a limited stylistic and emotional range—one which so many of her other performances imply is close to a default alternative for her. If she had won the Oscar, I am sure I'd feel cranky that such a flawed part with relatively little screen-time in such a bulging, often listless picture had copped her the statue.

A winless nomination, though, seems like a fitting way to commend Signoret for actually thriving with an assignment that almost begs for failure. I wouldn't want to put the performance in a time capsule, but I would want to show it to any number of actors who think that stock, sentimental, or politically signboarded roles can't be rendered in a way that is smart and moving, and through congenital understatement, no less. Sometimes Signoret is an ace deflector of bathos, as when she receives the information about the Werner character's lethal heart condition by futzing with a stray thread in the tablecloth: who among us, much less in Hollywood, would have resisted this call for moist horror, the frozen, welling close-up that screams, Pity him! Pity me! Sometimes, too, she plays right into the contrived emotionalism of the part, combing her fingers through Werner's hair or firing a deep, searching look into his eyes—and in these moments, her success involves modulating the degrees of sentimentality, not substituting a less expected affect or a bit of actorly business in its place. I'm guessing the Countess would have disliked the film's glossy, melodramatized version of political messaging, and for all I know, Signoret did, too, even though she's humane enough not to judge the Countess for her own moments of grandiloquent feeling. It's an ersatz film, but a very good performance, and in its dignified resourcefulness, an even better acting lesson.

The Best Actress Project: 1 More Down, 22 to Go

Labels: 1960s, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor, France, Simone Signoret

7 Comments:

This is the type of movie I usually love but Ship of Fools really left me cold. Most storylines didn't work and José Ferrer, so amazing in his Oscar-winning performance, gives one of the most awful performances I ever witnessed.

Still, Oskar Werner and Simone Signoret were able to get the most out of their material and managed to be the only interesting thing in this film. I would rank the 1965 nominees like this:

1. Elizabeth Hartman (I'm usually alone with this opnion)

2. Julie Christie

3. Julie Andrews

4. Samantha Eggar

5. Simone Signoret

I have done this year on my blog already (I would be very honored if you found some time to check it out) so I am using this opportunity to shamelessly make some commercial for myself. :-)

I would have prefered if they had given the Best Picture nomination to A Patch of Blue instead of this but Ship of Fools is, of course, just the type of movie the Academy loves.

I know it probably goes without saying, but I still feel the need to note that Katherine Anne Porter's original novel possesses a subtlety, wit, and nuance (despite its archetypal characters) that Stanley Kramer would never have been capable of applying here. Just wanted to add that, since you didn't mention anything about the source material, and since Porter is one of the under-recognized greats.

I love your assessment of Signoret's performance. It definitely is has a narrow range, but sometimes over-restraint is so, so much better than its histrionic alternatives.

For me, George Segal's performance is the most grating of all.

Hmm. I had a look at the 'Ship of Fools' trailer after reading this and... I have to admit, in full awareness of it being a Stanley Kramer film, I'm intrigued. My head says no, but my ensemble drama loving heart says different.

Stanley Kramer seems a faintly tragic character to me these days. Mark Harris's 'Scenes from a Revolution', which follows him from the aftermath of this film through to 'Guess Who...''s success, presents him as a guy who thinks himself as a rebel and a genuine progressive, and just can't understand why everyone else thinks he's such a square.

I love this write up, partly because it helps me reconcile my feelings about Signoret's performance in 'Room at the Top' (the only thing I've seen her in). Her knack for underplaying provides emotional weight to that film in much the same way as it seems to do here, even as the odd cadences of her english and the lacunae in the script render her character oddly hard to get to grips with (I mean, what is she doing in such a stuffy provincial town in England?) I'd love to know what you think of the film, Nick, and Signoret in it.

I watched Ship of Fools and...well, I'm alive and typing this now. I guess the fact that I didn't inflict pain on myself during this train wreck of a movie is enough of an endorsement. Ship of Fools wasn't even entertainingly bad, just 2.5 hours of insufferable boredom and misguided liberalism packaged together with one of the oddest "all-star" ensembles ever put together. I wasn't too taken with Werner and Signoret, though I can see the points you make in your piece. They weren't as bad as José Ferrer, yet I felt like their storyline added to the tedium rather than make it come alive (like, say, Vivien Leigh's). In a different film, something could have possibly been made out of their work, but in Ship of Fools I would only give them one star each.

(And you are so right to point out that downright strange intro and concluding narration from Michael Dunn. As soon as he turned to the camera and said that, I knew it was going to be a loooooooong movie).

Interesting write-ups, Fritz! I agree that Ferrer is barely tolerable in this part, but I'm often in that camp when it comes to him. (I haven't seen Cyrano.) I should have a second look at A Patch of Blue some time on your recommendation, but the whole conceit just seemed so strained to me, and Shelley Winters has got to be among the least deserving winners of that category. But, I liked Hartman.

@Waukegan: Thanks so much for the comment and the nice words - as always, especially encouraging coming from a new commenter. I am not a fan of Segal here, either. And as for Porter: yes it's worth restating that the massively long book, which I haven't read, was a critical sensation and it sold bushels upon bushels of copies. Porter herself expressed misgivings about it for most of her life after writing it, but even without having read that particular work, I feel comfortable assuming that it's a richer, riskier work than the film Abby Mann and Stanley Kramer made out of it.

@Laika: I just re-viewed Room at the Top a few weeks ago in advance of Ship of Fools, and I liked Signoret better than I had remembered. Watching it for the first time ten years ago, I was put off by her physical stiffness, her halting fluency in English, and the film's and the actress's combined presentation of an older woman's bruised wisdom about sex, in a way that crossed the border too often into cliché. She seemed to have more shadings and a bit more wit this time around, though it still seems like acting in English—and acting opposite Laurence Harvey, the poor thing—hem her in. Ship of Fools has an even more dubious role in some ways but she seems much looser and cleverer in it; I almost wish she'd filmed them in the opposite order, and had someone more like Werner in the lead for Room at the Top, to see how far she might have taken that role. (You've heard they're about to make Pictures at a Revolution into a documentary, yes?)

@Dame James: That opening address from Michael Dunn really is an immediate buzzkill, isn't it? I happily return you the same favor you did me: I appreciate you giving me the benefit of the doubt on my response, and I can easily imagine finding the film and these performances as turgid and unrewarding as you did. I am surprised how much Werner and Signoret got to me, especially given the vehicle they were stuck with.

I agree that Shelley Winters is among the least deserving winners. The whole movie has such a fairy-tale aspect (Hartman as the suffering princess, Winters as the evil mother and Poitier as the (no pun intended) white knight) that it gives Winters nothing else to do but scream around and show how evil she is without every trying to make her character understandable or anything.

But Hartman really rose to the occasion and gave such a wonderful and heartbreaking performance as the suffering princess!

Oh, and thanks for stopping by at my blog! My reviews are obviously not nearly as explicit and well-written as yours, but I love watching these nominated performances and movies and having a blog is a nice way to get some distraction from all the other duties of life.

Anyway, I am glad that you like Simone in Room at the Top a bit better now. This is one of the performances I am never really 100% sure what to think about. Sometimes I think she is amazing, sometimes I think she doesn't really do anything but in the end, her dignified portrayal that is so different from other performances of these kind of characters won me over. Oh, and I think that Laurence Harvey is great in this movie - it's the only time his stiff acting style works because that's what the character needs (and I also find him strangely attractive...). But I think his best performance was in The Munchurian Candiate where he was surprisingly effective and totally unlike anything he's done before.

Post a Comment

<< Home