When I think about

Michelle Pfeiffer, I think about

Nathaniel, and when I think about

Nathaniel, I think about how much he hates it when actresses muffle their natural beauty or, worse, actively dowd themselves down in order to chase an Oscar. I don't know whether he already harbored such animus toward this practice when Pfeiffer, his favorite actress, scored her first two Oscar nominations for two of her most radiant, self-consciously sexy turns in

Dangerous Liaisons and

The Fabulous Baker Boys, or whether it was thus Pfeiffer herself who instilled in his mind that one

can be preternaturally exquisite

and act terrifically

and find a berth on Oscar's ballot... even if, you know, you maybe can't actually win. I'm sure Nathaniel hates it that Michelle lost to Geena Davis in

The Accidental Tourist and Jessica Tandy in

Driving Miss Daisy, but if, on either occasion, Michelle had lost to, say, Charlize Theron in

North Country or Hilary Swank in

Million Dollar Baby, I'm sure we would all still be breathing the ash from his own spontaneous combustion.

Those two performances as well as Michelle's nominated work in the somewhat underrated

Love Field are all wonderful, but at risk of prompting Nathaniel's ire, my two favorite Pfeiffer performances both sort of wander down that garden path of cosmetic humility that customarily drives him a little crazy. Then again, when Michelle dresses down or slings hash or wears flannels or lets the tresses go unwashed, she never does it in a way that betrays any false exhibitionism (not to mention that she is never less than ravishing). She never chases Oscar, even when she's cast in a part that invites some showboating; she's too ego-less of a performer to take that approach, and beyond that, for me, her calling card as an actress is a laser-beam commitment to the severity and hard truths of her characters. No wig or costume, either frilly or frumpy, is ever going to get in the way of an emotional lucidity and an integrity like Pfeiffer's. She isn't, to me, the world's rangiest actress, or at least she doesn't seem so: some of her tics and inflections, especially that hard quality of her voice in extreme states of emotion, are a little predictable from role to role. And yet, when I sometimes get too comfortable with my assumption that Pfeiffer, however capable, works best in a confined register of parts—maybe because of her weird, recent predilection for undemanding soft-genre pics helmed by undistinguished directors—I look back over her filmography (often at some prompting on Nathaniel's site) and realize how unexpectedly she has popped up in some very disparate projects, and what new facets she has revealed in both her talent and her movies whenever she has traveled like that.

I'm staying mum about my favorite Pfeiffer performance, even though it's by many leagues my favorite, because it'll be coming up later—a good deal later—on my

countdown of favorite films, and I don't want to spoil

that fun. But my second favorite Pfeiffer performance is in

A Thousand Acres, a movie that engendered little affection or admiration upon its 1997 release, partly because Touchstone Pictures had no idea how to sell it, and partly because, sad to say, director Jocelyn Moorhouse (

Proof,

How To Make an American Quilt) had next to no idea how to make it. Working from Jane Smiley's terrific but tonally delicate novel, as loamy and tough and deceptively complex as the Iowan soil, the film version of

A Thousand Acres makes almost every conceivable mistake of packing in too much incident, editing according to inherited sequence rather than any specifically filmic vision, shamelessly intercutting very different takes within scenes (a true nightmare of anti-continuity), and letting a lot of well-cast actors either flail about (Lange, Robards) or dully congeal (Anderson, Leigh) because they don't seem to be getting any direction.

But then there's Pfeiffer, cast as the watchful and vengeful sister Rose, the Regan to Lange's Goneril, except that the movie's forcing of perspective through Lange (aka Ginny) and the sisters' crucial imbalances of knowledge and motivation basically shift all the nervy but righteous vindictiveness onto Pfeiffer. She can handle it. Boy, can she. From the moment you meet her, whipping up Salisbury steak in a casserole dish and un-self-consciously inhabiting a farm kitchen, Pfeiffer's eyes have got a mean tint of steel, and they seem even wider and more dilated than usual. Her character has just survived a bout with breast cancer, and is still getting acclimated to her mastectomy. She bears an uncertain relation to a handsome prodigal son (Colin Firth's Jess Cagle) who has just returned to Zebulon County, and she seems to bristle around her father (Robards), even when she's superficially making nice, even before the Shit Hits The Fan. Just watching Pfeiffer sitting in a lawn chair at the potluck dinner in the opening scene—legs splayed, elbows and neckline precipitously angled, dry ice in her eyes, while Lange perches with birdlike decorum by her side—it's clear that all the energy and friction in the film is gestating inside her body, her inner abacus of justice and, mostly, injustice.

As the revelations unfold, Pfeiffer stays within her simmering glory, even as the ramshackle editing and august but ill-situated photography show no real knack for capitalizing on the performance. The convolutions of Smiley's plotline, which feel so lean and hewn in the context of her prose, find their equivalent in Pfeiffer's taut but unembellished delivery. A lot of the biggest secrets are hers to reveal, but they're terrible secrets, and Pfeiffer's Rose takes an almost unseemly pleasure in bringing them forward. Even as the pendulum of moral right keeps swinging her way, we feel less and less comfortable with her, and we wonder how much we should trust her; Lange, usually so good at watercolor gradations and coiled psychologies, doesn't come anywhere near to where Pfeiffer does with a much less intricate approach. Wondrously, when Rose actually starts to break all kinds of ethical pacts, even those with her sister, we start to like her

more: the actress's ironic management of empathy and outrage far exceeds what script-writer Laura Jones has achieved. All of this comes together in Rose's climactic monologue, delievered from a cot in a cancer ward, beneath an awful "cancer patient" wig, and amidst a chapter of the film that, even by its own poorly managed standards, feels listless, unformed. Pfeiffer's Rose has to list all the ways in which she has failed at life, but she preserves an enormous and wounding pride at her categorical refusal to gloss or deny: "I saw," she says, and it's the kind of pared-down screenwriting phrase that usually dies up there on the screen, but Pfeiffer brings it fully across. You wish there were more than half a movie around her, but there's certainly a whole movie

in her, and it's the one you wind up remembering.

Farm wife? Cancer patient? Gingham? Dust of the plains? Big closing speech? Yep, all that, and still no Oscar nod for Pfeiffer, or even a whisper of a chance, even in the bum year for lead actresses that was 1997. Even at the Golden Globes, where the reaching to fill the category was an audible moan in the ballroom, it was Lange who scored what Holly Hunter so memorably described as a "Hamburger Helper nomination." I didn't get it then, and I don't now, but you never get the sense that Pfeiffer cares about these sorts of things. And why should she, with her work so amply and deftly behind her? She grasped the role. She co-produced the film. She held fast under poor stewardship and among struggling colleagues. She put it over. She saw. Now you go see. (And go

here for more posts in Nathaniel's

Pfeiffer Blog-a-thon, on this, the eve of her 48th birthday. That's eleven years older than

Gillian, and she's still a vision!)

Labels: 1990s, Blog Buddies, Blog-a-thons, Michelle Pfeiffer

Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

When I think about

When I think about  While an oft-promised DVD collection from Palm Pictures remains a dream perpetually deferred, I have only my two-year-old recollections of Barney's formidable imagery and curiously interwoven "plots" to write from. Of course, the whole reason why the Cremaster Cycle ranks so high on this list is that Barney's outlandish mise-en-scène, forever emphasizing the organic, the amorphous, the massive, the adhesive, and the fluorescent in quite literal ways, also retains those very qualities in my memory. I saw the movies in superficially "numeric" order (i.e., 1 and 2 on one night, 3 the next, and 4 and 5 after that), but even following that schema, you implicitly sense that 4 and 1, the first films produced, supply the erstwhile Rosetta Stones to what more fully follows. These, the shortest installments, condition the viewer into the remarkable plasticity of Barney's visions, his outré cosmetic mutations of his own body, his recurring propensity for gonadal tropes and visual puns, and his fusion of mass-cultural signifiers like zeppelins, stadiums, land-speed races, and flight attendants with his carefully considered though highly subjective apprehensions of specific occult histories: drawn from the Isle of Man in Cremaster 4, but also from Hungary, Utah, and New York City in subsequent iterations. Both within each movie and across the whole series, Barney expectorates a kind of gestalt system that no one can comfortably articulate—not even he, I suspect, based on the "synopses" at the entrancing but opaque Cremaster

While an oft-promised DVD collection from Palm Pictures remains a dream perpetually deferred, I have only my two-year-old recollections of Barney's formidable imagery and curiously interwoven "plots" to write from. Of course, the whole reason why the Cremaster Cycle ranks so high on this list is that Barney's outlandish mise-en-scène, forever emphasizing the organic, the amorphous, the massive, the adhesive, and the fluorescent in quite literal ways, also retains those very qualities in my memory. I saw the movies in superficially "numeric" order (i.e., 1 and 2 on one night, 3 the next, and 4 and 5 after that), but even following that schema, you implicitly sense that 4 and 1, the first films produced, supply the erstwhile Rosetta Stones to what more fully follows. These, the shortest installments, condition the viewer into the remarkable plasticity of Barney's visions, his outré cosmetic mutations of his own body, his recurring propensity for gonadal tropes and visual puns, and his fusion of mass-cultural signifiers like zeppelins, stadiums, land-speed races, and flight attendants with his carefully considered though highly subjective apprehensions of specific occult histories: drawn from the Isle of Man in Cremaster 4, but also from Hungary, Utah, and New York City in subsequent iterations. Both within each movie and across the whole series, Barney expectorates a kind of gestalt system that no one can comfortably articulate—not even he, I suspect, based on the "synopses" at the entrancing but opaque Cremaster

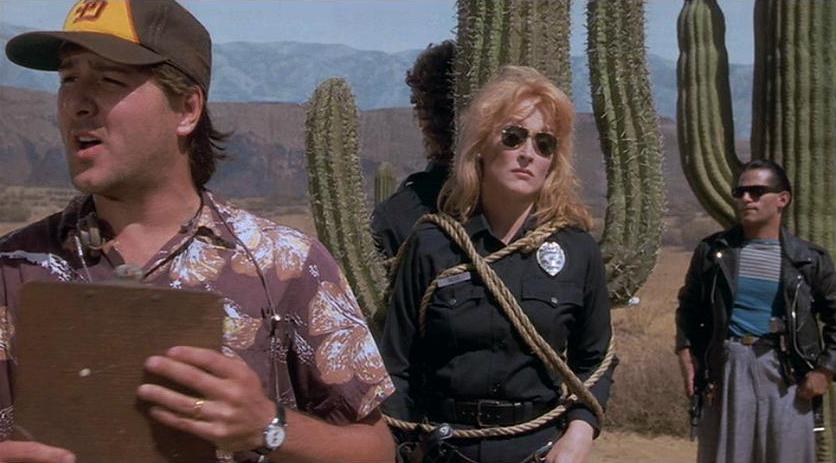

Postcards from the Edge hails from that period in Streep's career when she suddenly and understandably appeared apprehensive about forever playing pietàs and martyrs and wailing women from across the Earth's four corners. She had a Funny Period the same way Picasso had a Blue one, and though I haven't actually seen any of its other avatars (She-Devil, Defending Your Life, Death Becomes Her), her work in Postcards is so lively in detail that, again, you feel like you're getting several performances for the price of one. Meryl tokes up, she zones out, she trips, she sings twice, she shoots guns twice. But the real action is in the shifting sands of her face and her tiny symphonies of physical accents, whenever she's about the deceptively simple business of selling a line or a scene, or even a fellow actor's performance. Watch what a comic tour-de-force she finds just by crouching among a wire-rack of costumes on a movie-set, her eyes and her relative posture our only inlets into a twelve-tone coloratura of comic humiliation. Waking up, unexpectedly, in a rehab center, she parses out into multiple comic beats what many actors would fold or purée into a single affect: her dazedness, her breath, her shame, her fright, the blinding whiteness of the light and the room, the puzzling discovery of a plastic hospital bracelet around her arm, her dawning recognition that news of her predicament has certainly, already sprinted to undesired destinations. Carrie Fisher has filled her autobiographical script with choice one-liners and her trademark sensibility for observing life askance. "I have feelings for you," confesses a sun-kissed Dennis Quaid, to which Streep responds, "Well, how many? More than—two?", and while the line is a great gift to her (and there's way, way more where that came from), her muffled, almost foggy playing of it is a cadeau to Quaid, an earnest tryer who rarely knows, and certainly didn't know in 1990, how to anchor a scene or vary its rhythm. Streep forces him to shake things up, just like she keeps Shirley MacLaine's campy grandiloquence on a liberal but certain leash, letting her do her Thing, even getting her own zappy charge out of it, but also keeping everyone in service of the movie, especially of Fisher's voice. Like Streep, Fisher is possessed of a sophisticated hamminess that she isn't at all bashful about trotting out, so it's no surprise that the two women are such ample enthusiasts and protectors of each other. Fisher's overriding and self-analytical theme, that she has no idea who she is or who she should be, or whether those two concepts even remotely go together, also creates a winning ironic frame for Streep's own chameleonism: watching her change shape and mental fabric, even within seconds, weds the familiar pleasures to some new questions about exhibitionism and avoidance.

Postcards from the Edge hails from that period in Streep's career when she suddenly and understandably appeared apprehensive about forever playing pietàs and martyrs and wailing women from across the Earth's four corners. She had a Funny Period the same way Picasso had a Blue one, and though I haven't actually seen any of its other avatars (She-Devil, Defending Your Life, Death Becomes Her), her work in Postcards is so lively in detail that, again, you feel like you're getting several performances for the price of one. Meryl tokes up, she zones out, she trips, she sings twice, she shoots guns twice. But the real action is in the shifting sands of her face and her tiny symphonies of physical accents, whenever she's about the deceptively simple business of selling a line or a scene, or even a fellow actor's performance. Watch what a comic tour-de-force she finds just by crouching among a wire-rack of costumes on a movie-set, her eyes and her relative posture our only inlets into a twelve-tone coloratura of comic humiliation. Waking up, unexpectedly, in a rehab center, she parses out into multiple comic beats what many actors would fold or purée into a single affect: her dazedness, her breath, her shame, her fright, the blinding whiteness of the light and the room, the puzzling discovery of a plastic hospital bracelet around her arm, her dawning recognition that news of her predicament has certainly, already sprinted to undesired destinations. Carrie Fisher has filled her autobiographical script with choice one-liners and her trademark sensibility for observing life askance. "I have feelings for you," confesses a sun-kissed Dennis Quaid, to which Streep responds, "Well, how many? More than—two?", and while the line is a great gift to her (and there's way, way more where that came from), her muffled, almost foggy playing of it is a cadeau to Quaid, an earnest tryer who rarely knows, and certainly didn't know in 1990, how to anchor a scene or vary its rhythm. Streep forces him to shake things up, just like she keeps Shirley MacLaine's campy grandiloquence on a liberal but certain leash, letting her do her Thing, even getting her own zappy charge out of it, but also keeping everyone in service of the movie, especially of Fisher's voice. Like Streep, Fisher is possessed of a sophisticated hamminess that she isn't at all bashful about trotting out, so it's no surprise that the two women are such ample enthusiasts and protectors of each other. Fisher's overriding and self-analytical theme, that she has no idea who she is or who she should be, or whether those two concepts even remotely go together, also creates a winning ironic frame for Streep's own chameleonism: watching her change shape and mental fabric, even within seconds, weds the familiar pleasures to some new questions about exhibitionism and avoidance. In short, ten minutes into Without You I'm Nothing, everything has already gone wrong—although every viewer will probably cite a different epiphanic instant when the tawdry errancy of the film reveals its brilliant comic design, exposing that the uneasy laugh you're having at Bernhard's expense is actually the laugh she's having on you, and on herself, and on almost everybody. Like Margaret Cho's

In short, ten minutes into Without You I'm Nothing, everything has already gone wrong—although every viewer will probably cite a different epiphanic instant when the tawdry errancy of the film reveals its brilliant comic design, exposing that the uneasy laugh you're having at Bernhard's expense is actually the laugh she's having on you, and on herself, and on almost everybody. Like Margaret Cho's  My life on Fridays is the opposite of my students': I barrel outward for public excitement during the afternoon, and then laze inside the comfort of my own walls at night. After a long week of work, today has been a good day: I caught a 2:30

My life on Fridays is the opposite of my students': I barrel outward for public excitement during the afternoon, and then laze inside the comfort of my own walls at night. After a long week of work, today has been a good day: I caught a 2:30

As with The Crying Game, but working in an opposite direction, I have experienced a pretty notable swerve in my repsonse to In the Mood for Love. In this case, I have grown almost habituated, if such a thing is possible, to Love's rapturous mise-en-scène and its intricately woven sound elements, hypnotized and transported as I am by the miracle that is Maggie Cheung. I love the word "equipoise," but I wonder if it describes any single thing in the universe so well as it does Cheung's absolute and yet sensationally un-fussy control over the line of her body, the most minute calibrations of every feature, every lash. Sitting in a chair, casting her eyes over a newspaper, her posture is not an I or an S or an L, but some kind of sublime, pristine character missing from our alphabet. Her playing of scenes like Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow's evening out at a restaurant is suffused with an emotional urgency that is almost chemical, nowhere manifest and yet everywhere felt; by comparison, even such an accomplished telepath as Julianne Moore seems like she's doing handstands and flagging out semaphores in the somewhat analogous scenes in The End of the Affair. Other actors have dazzled in Wong's movies, though usually by sculpting themselves into ravishing emblems of cool like Brigitte Lin in Chungking Express or Carina Lau in Days of Being Wild, or black holes of devouring need like Leslie Cheung in Happy Together, or plaintive alter egos like Tony Leung in almost everything. But Cheung in In the Mood for Love exhibits an utter, respectful reverence for the art-object that Wong is creating around her, without ever seeming merely ornamental or rooting herself into any one attitude or affect. She is sad, resigned, perceptive, aroused, a good neighbor, a rattled wife, a creature of new and sudden impulse, a pilgrim returned to former haunts, and in every one of these guises, she has the clarity and soft color of blown glass, but also the veins and arteries of a human person.

As with The Crying Game, but working in an opposite direction, I have experienced a pretty notable swerve in my repsonse to In the Mood for Love. In this case, I have grown almost habituated, if such a thing is possible, to Love's rapturous mise-en-scène and its intricately woven sound elements, hypnotized and transported as I am by the miracle that is Maggie Cheung. I love the word "equipoise," but I wonder if it describes any single thing in the universe so well as it does Cheung's absolute and yet sensationally un-fussy control over the line of her body, the most minute calibrations of every feature, every lash. Sitting in a chair, casting her eyes over a newspaper, her posture is not an I or an S or an L, but some kind of sublime, pristine character missing from our alphabet. Her playing of scenes like Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow's evening out at a restaurant is suffused with an emotional urgency that is almost chemical, nowhere manifest and yet everywhere felt; by comparison, even such an accomplished telepath as Julianne Moore seems like she's doing handstands and flagging out semaphores in the somewhat analogous scenes in The End of the Affair. Other actors have dazzled in Wong's movies, though usually by sculpting themselves into ravishing emblems of cool like Brigitte Lin in Chungking Express or Carina Lau in Days of Being Wild, or black holes of devouring need like Leslie Cheung in Happy Together, or plaintive alter egos like Tony Leung in almost everything. But Cheung in In the Mood for Love exhibits an utter, respectful reverence for the art-object that Wong is creating around her, without ever seeming merely ornamental or rooting herself into any one attitude or affect. She is sad, resigned, perceptive, aroused, a good neighbor, a rattled wife, a creature of new and sudden impulse, a pilgrim returned to former haunts, and in every one of these guises, she has the clarity and soft color of blown glass, but also the veins and arteries of a human person. Probably not a great idea to rush myself to judgment on such a ruminative and atmospheric film, but who said reviewing films was a good idea? Short notes

Probably not a great idea to rush myself to judgment on such a ruminative and atmospheric film, but who said reviewing films was a good idea? Short notes  Watching The Crying Game now is nothing like the same experience, for any number of reasons. Both in my personal life and in the wider culture, the film's images of a gay watering hole and its verbal and visual rhetoric around homosexuality seem almost quaint. Maybe in 1992 The Crying Game already looked quaint to people who had actually visited a gay bar or a drag performance, or who had real-life honest-to-God queer acquaintances. As for me, I was watching from a vantage of such conjecture and fantasy that I remember feeling wholly seduced, not by the secrets but by the surfaces: how beautiful Dil was, how much I liked her form-fitting wine-colored suit and Miranda Richardson's heavy cable-knit sweater (thus commencing my 14-year affair with Sandy Powell), and best of all, how capably and, in my opinion, sophisticatedly the film interwove its sexual themes into other political arguments. In a film that, as far as I had been told, pivoted entirely on one big reveal, it seemed to me that The Crying Game was about sexuality only to the extent that it was about everything else that it was about. Captation, friendship across enemy lines, a lover's grief, unwelcome revenants from the past, hot and cool approaches to protest and subversion... The Crying Game didn't deny or derealize queer sexuality, but nor did it divorce sexuality from a bigger, gnarlier knot of human problems, and this, for me, was its Big Twist. As little as I had let myself really think about homosexuality, I had thought even less about terrorism and guilt and secret honor, and even less than that about how sexuality could bleed through, in, around, and as those other ideas. Similarly, as floored as I was by Jaye Davidson's performance as Dil—not his casting but his performance—and as therefore aggrieved as I was by Oscar's preference of Gene Hackman, I also clocked Adrian Dunbar's searing indignation, Stephen Rea's recessive sadness, Miranda Richardson's shifting web of motivations, and Jim Broadbent's unobtrusive whimsy as the barman. The Crying Game, just as much as Howards End the same year, was my introduction to great character acting; understandably, it took another year or two for me to recognize that people outside of Britain knew how to do this.

Watching The Crying Game now is nothing like the same experience, for any number of reasons. Both in my personal life and in the wider culture, the film's images of a gay watering hole and its verbal and visual rhetoric around homosexuality seem almost quaint. Maybe in 1992 The Crying Game already looked quaint to people who had actually visited a gay bar or a drag performance, or who had real-life honest-to-God queer acquaintances. As for me, I was watching from a vantage of such conjecture and fantasy that I remember feeling wholly seduced, not by the secrets but by the surfaces: how beautiful Dil was, how much I liked her form-fitting wine-colored suit and Miranda Richardson's heavy cable-knit sweater (thus commencing my 14-year affair with Sandy Powell), and best of all, how capably and, in my opinion, sophisticatedly the film interwove its sexual themes into other political arguments. In a film that, as far as I had been told, pivoted entirely on one big reveal, it seemed to me that The Crying Game was about sexuality only to the extent that it was about everything else that it was about. Captation, friendship across enemy lines, a lover's grief, unwelcome revenants from the past, hot and cool approaches to protest and subversion... The Crying Game didn't deny or derealize queer sexuality, but nor did it divorce sexuality from a bigger, gnarlier knot of human problems, and this, for me, was its Big Twist. As little as I had let myself really think about homosexuality, I had thought even less about terrorism and guilt and secret honor, and even less than that about how sexuality could bleed through, in, around, and as those other ideas. Similarly, as floored as I was by Jaye Davidson's performance as Dil—not his casting but his performance—and as therefore aggrieved as I was by Oscar's preference of Gene Hackman, I also clocked Adrian Dunbar's searing indignation, Stephen Rea's recessive sadness, Miranda Richardson's shifting web of motivations, and Jim Broadbent's unobtrusive whimsy as the barman. The Crying Game, just as much as Howards End the same year, was my introduction to great character acting; understandably, it took another year or two for me to recognize that people outside of Britain knew how to do this. Following the candy-colored trail from the mugging back into my normal life, I went to the eye doctor's office yesterday to get a prescription for new glasses, only to have Pawel the Optician tell me that I have

Following the candy-colored trail from the mugging back into my normal life, I went to the eye doctor's office yesterday to get a prescription for new glasses, only to have Pawel the Optician tell me that I have  Meanwhile, the Saints keep marching in, as yet another all-star in my life celebrates a birthday. Not Clementine, even though I suspect that her

Meanwhile, the Saints keep marching in, as yet another all-star in my life celebrates a birthday. Not Clementine, even though I suspect that her  Really, I blame the government, since I was up so late doing my taxes—why does the Connecticut Part-Year Resident form have to be so byzantine? But, my anger also lies with myself: tonight I lucked into an on-campus screening of a restored 35mm print of Victor Erice's

Really, I blame the government, since I was up so late doing my taxes—why does the Connecticut Part-Year Resident form have to be so byzantine? But, my anger also lies with myself: tonight I lucked into an on-campus screening of a restored 35mm print of Victor Erice's  Despite this spotty track record, Greenaway is a director who interests me tremendously; I'm not easily put off by someone who will work this hard to make such exquisitely eccentric objects, alternately impenetrable and rife with insinuations. Twice, his epic blends of the epicurean and the rectilinear have produced something that really floored me. Go figure, then, that my favorite of Greenaway's movies, The Baby of Mâcon, is the one that's still illegal in the United States, presumably because it's the one that comes close in its esoteric way to saying something that the United States needs to hear. Julia Ormond, happening upon a director even frostier than she is, comes wickedly alive as a hot-blooded French woman in a 17th-century village beset by famine, plague, and fallow fields. The only sign of new life in Mâcon is the pristinely beautiful baby that springs, incongruously, from Ormond's obese and haggard mother; boldly braiding her own self-interest into the town's thirst for a positive omen, she claims the flaxen-haired infant as her own virgin birth, and then seduces the local bishop's icily skeptical son (Ralph Fiennes) with the brazen magnificence of her lie and the voluptuous offering of her body. Every main character is paradoxically addicted to the ideal of holiness and the spark of carnality, leading to the sorts of perverse hypocrisies and self-gratifications that, in Greenaway's films, always get you killed in an especially macabre way. If anything, The Baby of Mâcon is even more lavishly mounted than most Greenaway pageants, and even more Artaudian in its sickening climax of violence. By staging the film as a Jacobean revenge drama—Sacha Vierny's camera glides fluidly but anxiously through the tense action, the offstage grumblings, and the murmuring audience of puffy aristocrats and smudgy commoners—Greenaway poses questions about voyeurism and cruelty that encompass both his viewers and himself, further layering the implications of this scary horror-melodrama about fundamentalism, superstition, jealousy, and prurience.

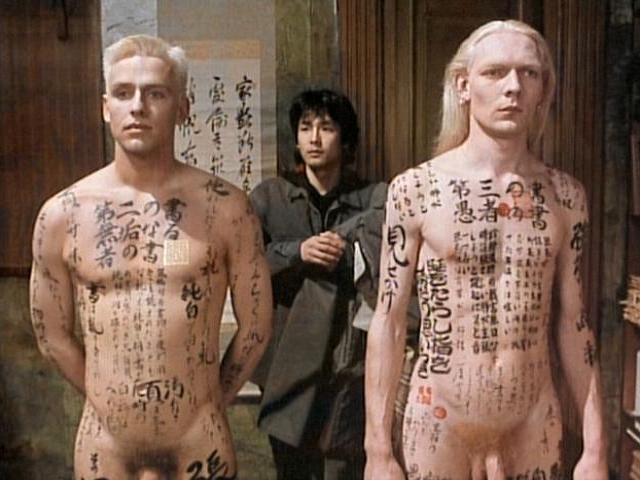

Despite this spotty track record, Greenaway is a director who interests me tremendously; I'm not easily put off by someone who will work this hard to make such exquisitely eccentric objects, alternately impenetrable and rife with insinuations. Twice, his epic blends of the epicurean and the rectilinear have produced something that really floored me. Go figure, then, that my favorite of Greenaway's movies, The Baby of Mâcon, is the one that's still illegal in the United States, presumably because it's the one that comes close in its esoteric way to saying something that the United States needs to hear. Julia Ormond, happening upon a director even frostier than she is, comes wickedly alive as a hot-blooded French woman in a 17th-century village beset by famine, plague, and fallow fields. The only sign of new life in Mâcon is the pristinely beautiful baby that springs, incongruously, from Ormond's obese and haggard mother; boldly braiding her own self-interest into the town's thirst for a positive omen, she claims the flaxen-haired infant as her own virgin birth, and then seduces the local bishop's icily skeptical son (Ralph Fiennes) with the brazen magnificence of her lie and the voluptuous offering of her body. Every main character is paradoxically addicted to the ideal of holiness and the spark of carnality, leading to the sorts of perverse hypocrisies and self-gratifications that, in Greenaway's films, always get you killed in an especially macabre way. If anything, The Baby of Mâcon is even more lavishly mounted than most Greenaway pageants, and even more Artaudian in its sickening climax of violence. By staging the film as a Jacobean revenge drama—Sacha Vierny's camera glides fluidly but anxiously through the tense action, the offstage grumblings, and the murmuring audience of puffy aristocrats and smudgy commoners—Greenaway poses questions about voyeurism and cruelty that encompass both his viewers and himself, further layering the implications of this scary horror-melodrama about fundamentalism, superstition, jealousy, and prurience. After the international PR disaster of The Baby of Mâcon, Greenaway's next film was the luxuriously synesthaesiac The Pillow Book, an absolute corker of a 90-minute movie that unfortunately continues for 45 more minutes, working hard in the process to numb and obliterate everything that is almost impossibly gorgeous in the preceding material. Vivian Wu plays Nagiko, a haughty Japanese model with an insatiable yearning for having calligraphy painted on her skin. Wu is a shrilly maladroit presence, and the premise wouldn't work at all if it weren't realized in such sinuous detail, but so it is. The Pillow Book lists two directors of photography, three production designers, four costume designers, and two calligraphers in the opening credits, and indeed, the movie comes closer than any other to constituting its own elaborate, absorbing museum—one where you're encouraged to sniff and caress the artwork, to strip the clothes off the models, to run the paint along your tongue like it's a spice. This unparalleled mise-en-scène, the creatively embedded frames, and the arresting sonic mix of Japanese pop, monastic chants, and avant-garde rock together yield a new kind of movie, a three- and almost four-dimensional environment. Customary film grammar hardly accounts for how the movie works, either when it's scoring or when it's flailing, and if its structural repetitions ultimately grow a bit tedious, its fearless peculiarity and almost aphrodisiac blend of skin, music, and curvaceous lettering make it worth digesting in multiple doses, even if they're small ones. (Click

After the international PR disaster of The Baby of Mâcon, Greenaway's next film was the luxuriously synesthaesiac The Pillow Book, an absolute corker of a 90-minute movie that unfortunately continues for 45 more minutes, working hard in the process to numb and obliterate everything that is almost impossibly gorgeous in the preceding material. Vivian Wu plays Nagiko, a haughty Japanese model with an insatiable yearning for having calligraphy painted on her skin. Wu is a shrilly maladroit presence, and the premise wouldn't work at all if it weren't realized in such sinuous detail, but so it is. The Pillow Book lists two directors of photography, three production designers, four costume designers, and two calligraphers in the opening credits, and indeed, the movie comes closer than any other to constituting its own elaborate, absorbing museum—one where you're encouraged to sniff and caress the artwork, to strip the clothes off the models, to run the paint along your tongue like it's a spice. This unparalleled mise-en-scène, the creatively embedded frames, and the arresting sonic mix of Japanese pop, monastic chants, and avant-garde rock together yield a new kind of movie, a three- and almost four-dimensional environment. Customary film grammar hardly accounts for how the movie works, either when it's scoring or when it's flailing, and if its structural repetitions ultimately grow a bit tedious, its fearless peculiarity and almost aphrodisiac blend of skin, music, and curvaceous lettering make it worth digesting in multiple doses, even if they're small ones. (Click

Happy 47th birthday to

Happy 47th birthday to

Tilda Swinton stars as a hotshot lawyer named Eve. Right off the bat, you can tell that subtlety isn't the movie's elected forte, and yet, why and how Swinton's character is an "Eve" is hard to pin down. A rising star on the legal circuit with a prestigious judgeship all but guaranteed to come her way, she embodies a mix of professional competence and self-alienation that isn't exactly unfamiliar—don't all professional women in American movies eventually realize that they don't know who they are?—and yet, because she's played by Swinton, Eve's unraveling doesn't feel conventional. Instead, it's a strangely out-of-body experience, navigated by the only Brechtian actress working in modern film, whose masklike and yet disarmingly lucid face always works in ironic tandem with her stiffly elegant body. Surrounding Swinton are a clutch of other women who were case studies and paragons in Dr. Louise J. Kaplan's original book (full title: Female Perversions: The Temptations of Emma Bovary), and whom the screenplay by director Streitfeld and co-writer Julie Hébert determinedly maroon somewhere between being characters and ciphers. Amy Madigan, a coiled and arrestingly spiteful actress, has her finest hour here as Madeleine, the black-sheep sister of Swinton's powerful up-and-comer. Madigan shoplifts a silk scarf with a memorable glower, she all but deliberately sabotages her sister's professional coronation, and she manages the neat trick of constantly messing everything up for everyone in the movie (including for herself) without sacrificing the audience's interest. Frances Fisher blowzes around as a good-time girl, Laila Robins is tearful as a dressmaker in a trailer, Paulina Porizkova strides through her scenes as an immaculately tailored rival of Swinton's, and Karen Sillas—an underrated and little-remembered presence from Tom Noonan's What Happened Was... and some Hal Hartley films—stands toe-to-toe with Swinton as one of two lovers whom the bisexual Eve keeps stringing along. Marcia Cross puts in a mysterious cameo, basically the same shot repeated several times, as Swinton and Madigan's abused mother, and an unknown, almost androgynous waif named Dale Shuger slides even more slivers of unease beneath your skin as Edwina, a teenaged girl who flees from all the parodic female visions around her, retreating into an intensely private life of scarring her flesh and burying the pads and tissues stained with her ovulated blood.

Tilda Swinton stars as a hotshot lawyer named Eve. Right off the bat, you can tell that subtlety isn't the movie's elected forte, and yet, why and how Swinton's character is an "Eve" is hard to pin down. A rising star on the legal circuit with a prestigious judgeship all but guaranteed to come her way, she embodies a mix of professional competence and self-alienation that isn't exactly unfamiliar—don't all professional women in American movies eventually realize that they don't know who they are?—and yet, because she's played by Swinton, Eve's unraveling doesn't feel conventional. Instead, it's a strangely out-of-body experience, navigated by the only Brechtian actress working in modern film, whose masklike and yet disarmingly lucid face always works in ironic tandem with her stiffly elegant body. Surrounding Swinton are a clutch of other women who were case studies and paragons in Dr. Louise J. Kaplan's original book (full title: Female Perversions: The Temptations of Emma Bovary), and whom the screenplay by director Streitfeld and co-writer Julie Hébert determinedly maroon somewhere between being characters and ciphers. Amy Madigan, a coiled and arrestingly spiteful actress, has her finest hour here as Madeleine, the black-sheep sister of Swinton's powerful up-and-comer. Madigan shoplifts a silk scarf with a memorable glower, she all but deliberately sabotages her sister's professional coronation, and she manages the neat trick of constantly messing everything up for everyone in the movie (including for herself) without sacrificing the audience's interest. Frances Fisher blowzes around as a good-time girl, Laila Robins is tearful as a dressmaker in a trailer, Paulina Porizkova strides through her scenes as an immaculately tailored rival of Swinton's, and Karen Sillas—an underrated and little-remembered presence from Tom Noonan's What Happened Was... and some Hal Hartley films—stands toe-to-toe with Swinton as one of two lovers whom the bisexual Eve keeps stringing along. Marcia Cross puts in a mysterious cameo, basically the same shot repeated several times, as Swinton and Madigan's abused mother, and an unknown, almost androgynous waif named Dale Shuger slides even more slivers of unease beneath your skin as Edwina, a teenaged girl who flees from all the parodic female visions around her, retreating into an intensely private life of scarring her flesh and burying the pads and tissues stained with her ovulated blood.