Actress Files: Irene Dunne

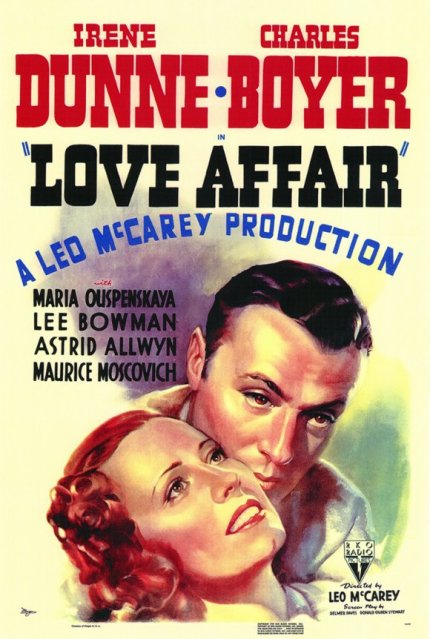

Irene Dunne, Love Affair

Irene Dunne, Love Affair★ ★ ★ ★ ★

(lost the 1939 Best Actress Oscar to Vivien Leigh for Gone with the Wind)

Why I Waited: As with Lee Remick, checking off this performance meant signing off on a top-drawer roster, and I was sorry to see it go. Affection for Dunne, and hearsay that this was her favorite among her own movies, only amplified the anticipation.

The Performance: The first thing Irene Dunne does in Love Affair is say "I beg your pardon" through a porthole-shaped window connecting an enclosed hallway on a cruise-liner to an outdoor promenade. Why is that special? Because she says it in the quick, peremptory way that you'd actually say "I beg your pardon" in real life, and not as you would say it to a soulmate disguised as a stranger, whom you were meeting at the outset of a classic romance. Her character is called Terry, and the reason she has been hailed into conversation by Charles Boyer's Michel is that a gust of wind has just blown a telegram from his fiancée out of his hand and through this window; he's asking that she pass it back. Sizing up this charismatic, brutely handsome Continental and enjoying his embarrassment, especially after taking a glance at the ripely romantic telegram, Terry teases him to prove that the telegram is really his, forcing him to recite certain details. She's having a passing lark, like a woman who is used to entertaining herself on the spur of the moment with cheeky little dares and parries. She's also baldly flirting with someone she's never met, whom she can only see from the neck up, and about whom the only things she knows are 1) that he's engaged and 2) that he's rich enough to be with her on this boat. Within an instant, she seems like a pretty rare bird, and she has sized him up as one, too, ascertaining as well that they belong to the same flock. Thus, they have immediate bonafides as movie characters, and the makings of a high-flying, promising couple. Yet she's also the kind of woman who can say "I beg your pardon" like she's any woman, anywhere, talking to anyone.

Irene Dunne's appeal rests on such unusual fusions of the ordinary, the glamorous, and the subtly but defiantly odd. There are shots fairly early in Love Affair, while she's encased in a huge, armoire-shaped fur coat and coiffed in a matronly updo, when she looks a bit grandmotherly for a romantic lead. You can see why, as early as Cimarron, when she was eight years younger than she is in Love Affair she was so easily adaptable into old-age makeup. (She was in fact 41 when Love Affair opened, which should inspire a lot of Hollywood women, as well as their fans.) Dunne's air of strangeness has to do with how quickly she presumes familiarity and sets about seducing and needling men who are more "obviously" attractive than she is: Cary Grant, Charles Boyer, John Boles, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. She takes liberties, verbally tickling them, looking fully confident that her rectangular smile, her mischievous gaze, her nutty hats, and her habit of throwing arch or exhausted "ah"s and "mm"s into her dialogue are as fetching as anything these matinée idols bring to the table. In her screwball and pseudo-screwball performances, but even in roles like the one in Love Affair, she comes across as a sort of tenuously acculturated version of Katharine Hepburn's Susan from Bringing Up Baby, pleased as punch to start a little trouble at any given moment, and it's both perplexing and funny that she can nonetheless transform in a second into a completely credible society type. One minute, in Love Affair, she's throwing a photographer's pictures into the ocean and having a dry, self-satisfied little chuckle about it. Three beats later, she's embodying the kind of woman who might need to worry if the gossip columns catch her scent, who would feel bad about breaking a rule if it hurt someone, or drew agitating attention to herself. Even if you don't know that Dunne was raised from solid, devout, Republican stock, you can feel her bone-deep handle on "proper" behavior in her performances, even the ones—which is most of them, especially in the 30s, whether she's laughing, yearning, or crying—where she's one way or another tossing dart after dart at the bulls-eye of respectability.

Stanley Cavell famously wrote in Pursuits of Happiness that, of all the great screwball heroines, Dunne is the one whose movies suffer most if you can't jive to her idiosyncratic appeal, even as she's also the actress who's wry and eccentric in just the sorts of ways that might annoy a lot of viewers. Compared to Theodora Goes Wild or Joy of Living or My Favorite Wife or even The Awful Truth, Love Affair strikes me as the film from Dunne's peak period where it's hardest to imagine not falling for her character, but it's wonderful to discover that this isn't because it's a boring or safe performance. Maybe Dunne knows that after playing so many daffy miscreants, it's something of a risk for her to play so many of Terry's feelings semi-straight, whether falling rather suddenly for Michel, or realizing their attraction to each other has an 8©-day lifespan until the ship reaches port. She takes undisguised and unironic pleasure in meeting Michel's stately but smiling grandmother (Maria Ouspenskaya, who also plays the ship) and bids her a full-bodied, close-to-tears farewell as they're prancing out of her house. The script even requires that Terry duck into the matron's private chapel and take a few moments out for God. Rudolph Maté lights this scene like a meaningful interlude of piety, catching Dunne and her all-white outfit in a nimbus of angelic light, and her look of simple, religious earnestness is as welcome a surprise as the solemn, perceptible agnosticism on Boyer's brow. Love Affair, a famous movie whose plot is even more of a cultural mainstay care of the 1957 remake An Affair to Remember, eventually depends on a big, bathetic plot contrivance and needs the ballast of plausible, un-tricked-out acting to avoid total shamelessness, and to pack the enormous charge that it has for decades of viewers. A lot of actors, even good ones, would seek to establish plausibility and overcome the big narrative stunt by expressing ardor, anticipation, devastation, and climactic, chin-up martyrdom with such surging commitment that the penny-romance conceits get buoyed along by sheer emotional force. We'll call that the Whitney Houston way to play the part, and make no mistake that I(IIIII-ee-IIIIII-ee-IIIIII....) can be a sucker for that stuff.

Stanley Cavell famously wrote in Pursuits of Happiness that, of all the great screwball heroines, Dunne is the one whose movies suffer most if you can't jive to her idiosyncratic appeal, even as she's also the actress who's wry and eccentric in just the sorts of ways that might annoy a lot of viewers. Compared to Theodora Goes Wild or Joy of Living or My Favorite Wife or even The Awful Truth, Love Affair strikes me as the film from Dunne's peak period where it's hardest to imagine not falling for her character, but it's wonderful to discover that this isn't because it's a boring or safe performance. Maybe Dunne knows that after playing so many daffy miscreants, it's something of a risk for her to play so many of Terry's feelings semi-straight, whether falling rather suddenly for Michel, or realizing their attraction to each other has an 8©-day lifespan until the ship reaches port. She takes undisguised and unironic pleasure in meeting Michel's stately but smiling grandmother (Maria Ouspenskaya, who also plays the ship) and bids her a full-bodied, close-to-tears farewell as they're prancing out of her house. The script even requires that Terry duck into the matron's private chapel and take a few moments out for God. Rudolph Maté lights this scene like a meaningful interlude of piety, catching Dunne and her all-white outfit in a nimbus of angelic light, and her look of simple, religious earnestness is as welcome a surprise as the solemn, perceptible agnosticism on Boyer's brow. Love Affair, a famous movie whose plot is even more of a cultural mainstay care of the 1957 remake An Affair to Remember, eventually depends on a big, bathetic plot contrivance and needs the ballast of plausible, un-tricked-out acting to avoid total shamelessness, and to pack the enormous charge that it has for decades of viewers. A lot of actors, even good ones, would seek to establish plausibility and overcome the big narrative stunt by expressing ardor, anticipation, devastation, and climactic, chin-up martyrdom with such surging commitment that the penny-romance conceits get buoyed along by sheer emotional force. We'll call that the Whitney Houston way to play the part, and make no mistake that I(IIIII-ee-IIIIII-ee-IIIIII....) can be a sucker for that stuff.But Dunne takes the road of Dolly Parton, letting us know that she will always love Michel by allowing Terry an absolute candor around him, in mirth and passion and sorrow. She banks on the power of sharp, clear, modest phrasing to signal concealed depths, rather than plunging right into them and dragging us along. Some actors congenitally suggest that one mustn't play two emotions at once or can only do so by pointing huge arrows at your own double-meanings. Dunne, though, manages a tinge of sexiness while being briskly funny, adopting a slurry Mae West timbre while dissuading Boyer from confiding his secret romantic angst. "I'm really not very good at that sort of thing," she drawls. "I talk a lot." There's no double-meaning here, just a tangy friskiness that packs more into the line than it's asking. When Ouspenskaya's benevolent dowager worries that Michel has missed out on romantic partnership because "he's been too busy...," Dunne is the perfect actress to complete the sentence ("...living?") in a way that preserves the tactful euphemism, appropriate to speaking with one's elders, while grinning that she knows just what "living" involves in this context, and that she's the last person to frown upon it. "I guess you and I have been more or less used to a life of pink champagne," she confides to Boyer's playboy, without an ounce of the censorious, compulsory Hollywood pretense that the rich, or at least the best among them, don't care about their money. Dunne's Terry is thrilled to have money, and aware that it won't be comfortable to proceed without it, even as she's sportingly up to the fresh challenge of earning her own.

An actor can't give us such complete frameworks for grasping a character's complex feelings, especially those that are germane to the whole plot of the film, without being able and willing at crucial times to tell a different story with her face than with her voice, or able to turn nimbly from one affect to another, as when Terry follows her dreamy citation of her father saying "Wishes are the dreams we dream when we're awake" with the dry-gin chaser of "He drank a lot." In a brilliant bit of direction, perfectly enacted by Dunne, Terry outlines the famous meet-atop-the-Empire-State-Building stratagem for rendezvousing with Michel six months in the future as though she really has lost her heart to him and she enjoys a good romantic cliffhanger... and at the same time, she's clutching her arms and bobbing up and down like it's very cold out there on the deck, so she ends the scene with a clipped, over-the-shoulder "Take care of yourself" as she dashes inside for warmth. Love Affair has enough of its barrels aimed at the summit of screen romance that Dunne, Boyer, and McCarey know that not every shot they take needs to hit that same target. We might even believe the scenario more fully, or care about the characters more richly, if their layers and peccadilloes drive the narrative, rather than allowing the abstract goal of just smashing our hearts dictate everything they say and do, and every way they do and say it.

Why not five stars, then? Well, the final third of Love Affair, where The Whitney Approach would really start going for broke—and I presume, sight unseen, that this is just what Deborah Kerr attempts—is a little less hospitable to Dunne. Her genius lies primarily in timing and in creative, multi-faceted interactions with her co-stars. Therefore, long sequences of her singing unmemorable songs in close-up, while Terry builds up her nest-egg as a nightclub chanteuse, prove an unexpected advert for Dunne's opera-trained soprano but otherwise don't give her anything to do creatively. I love her typical counter-intuition in diluting the performance just when so many actors would start pumping up the volume, and she is a godsend in the moment when Terry and Michel unexpectedly meet in a theater, each in another person's company, and in the short taxi-cab scene just afterward, when she insists as conversationally as possible that she really doesn't want Michel knowing about her waist-down paralysis. But in other, neighboring scenes, playing the ukulele and singing with a cadre of orphans, or negotiating for a job with the orphanage director, she looks a little bored without a more inspiring scene partner. One sign is the deflated way in which she reads some of her lines, even if this deflation is meant to register the ebb in Terry's spirit following her accident. It's just as revealing, though, that in these scenes Dunne reprises some of her oldest standby mannerisms from other performances, like her mischievous grin, with one fingernail resting on her teeth. Not in every moment of an Irene Dunne performance does she look unreservedly involved in what's going on. There are flashes of this habit even in the long final scene with Boyer, where she emotes very movingly in some of her close-ups, but you still sense that she'd be thrilled to do a little more of the talking.

Still, Dunne succeeds memorably in being amusing and aroused and resilient and regretful and somewhere close to ideal in Love Affair, without almost ever taking the most predictable paths toward any of these goals. At 88 minutes, Love Affair itself is as succinct as she is, covering a lot of ground without needing a lot of time, and proving, in perfect sync with its leading lady, that sly and disciplined pithiness can be just as powerfully moving as extravagant excess. At the midpoint of the movie and again in the closing moments, Dunne has to recite a line concerning "the nearest thing to heaven"—I'm sure you can guess what that is—and the sentiments feel too inescapably on-the-nose for a performer who so clearly prefers to arrive sideways into a screenplay's designs, or to tell the audience what we expect to hear through a counter-harmonic approach that only Dunne would conceive. We don't need to hear about the nearest thing to heaven when, left to her own devices, and furnished the proper companions, she has such a sparkling track record for getting us there herself.

The Best Actress Project: 1 More Down, 9 to Go

Labels: 1930s, Best Actress, Four Stars, Irene Dunne

Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

Considered a bit differently, in movies like To Each His Own or her

Considered a bit differently, in movies like To Each His Own or her

The Constant Nymph, for me, doesn't settle the question of how "good" an actress Fontaine finally is. I still credit an exceptional combination of ingredients for managing to extract precisely what is most special about her in Rebecca and Letter from an Unknown Woman. What The Constant Nymph does, though, is bring me palpably 'round to Fontaine's side, feeling well-disposed toward the performance even in its shakier angles and passages, and deciding once and for all that 40s cinema would lose something without her missionary work on behalf of girlish dreamers and piners. Nymph plays a bit like a rough draft for Unknown Woman. Here again, Fontaine is in pigtails, acting less than her real age while she rhapsodizes about a Francophone pianist-composer, even if Charles Boyer passes under the memorably non-Gallic name of Lewis Dodd. We first meet Fontaine's Tessa Sanger dashing all over the rural cottage where she lives with her father and sisters, astir at the news that Lewis is paying the Sangers one of his occasional visits. Upon his arrival, she beams at him with a desire that she either doesn't yet understand as romantic love or just doesn't want to recognize as such. She is, after all, a schoolgirl, so the intergenerational dynamics of The Constant Nymph can be disconcerting, well beyond seeing 26-year-old Fontaine dashing about in pigtails and braids. But at least it's energetic dashing, with some Jo March flavor—though closer, for sure, to Ryder than to Hepburn.

The Constant Nymph, for me, doesn't settle the question of how "good" an actress Fontaine finally is. I still credit an exceptional combination of ingredients for managing to extract precisely what is most special about her in Rebecca and Letter from an Unknown Woman. What The Constant Nymph does, though, is bring me palpably 'round to Fontaine's side, feeling well-disposed toward the performance even in its shakier angles and passages, and deciding once and for all that 40s cinema would lose something without her missionary work on behalf of girlish dreamers and piners. Nymph plays a bit like a rough draft for Unknown Woman. Here again, Fontaine is in pigtails, acting less than her real age while she rhapsodizes about a Francophone pianist-composer, even if Charles Boyer passes under the memorably non-Gallic name of Lewis Dodd. We first meet Fontaine's Tessa Sanger dashing all over the rural cottage where she lives with her father and sisters, astir at the news that Lewis is paying the Sangers one of his occasional visits. Upon his arrival, she beams at him with a desire that she either doesn't yet understand as romantic love or just doesn't want to recognize as such. She is, after all, a schoolgirl, so the intergenerational dynamics of The Constant Nymph can be disconcerting, well beyond seeing 26-year-old Fontaine dashing about in pigtails and braids. But at least it's energetic dashing, with some Jo March flavor—though closer, for sure, to Ryder than to Hepburn.

So, let's get to that tour de force—and let's imagine getting this script and tracing this character on paper, pretending that we haven't witnessed everything that Evans does with it. A woman living alone, 76 years old, long ago abandoned by her husband and seldom visited by her son. She hears voices, probably as a projective coping mechanism after years of isolation, but this isn't the supernatural ghost story I had imagined. We barely hear the "whisperers" even when she does. Her flat is a rat's nest of newspapers, bundles, and empty milk bottles. Her only external errands are visits to a Christian charity for hymns and hot soup, furtive siestas in the library where she can warm her stocking feet on the pipes (tsk tsk, say the guards), and visits to the public-assistance office, where she inquires about huge, clearly imaginary windfall sums that we know are never coming, and pretends to "make do" for the time being with the tiny dispensations that represent her state allotment.

So, let's get to that tour de force—and let's imagine getting this script and tracing this character on paper, pretending that we haven't witnessed everything that Evans does with it. A woman living alone, 76 years old, long ago abandoned by her husband and seldom visited by her son. She hears voices, probably as a projective coping mechanism after years of isolation, but this isn't the supernatural ghost story I had imagined. We barely hear the "whisperers" even when she does. Her flat is a rat's nest of newspapers, bundles, and empty milk bottles. Her only external errands are visits to a Christian charity for hymns and hot soup, furtive siestas in the library where she can warm her stocking feet on the pipes (tsk tsk, say the guards), and visits to the public-assistance office, where she inquires about huge, clearly imaginary windfall sums that we know are never coming, and pretends to "make do" for the time being with the tiny dispensations that represent her state allotment.  Evans clearly has a complex and practiced take on old age, and is interested in the atmospheric and psychological tensions generated by slowing things down. Mrs. Ross doesn't whip from reveries to indictments to fogginess to paralysis with Three Faces of Eve suddenness. She's not interested in putting on a light show. The effect is closer to that of a cloudy crystal ball, in which one side of this woman emerges for a moment before singing back into the whited-out mist, from which some other face emerges a beat or two later, and often quite a different one. Mrs. Ross lags into weary dumbfoundedness, staring at nothing and not moving for a few moments in a row, before leaping with sudden dispatch to pound her broomstick against her ceiling, in protest of the upstairs neighbors and their noisiness. She casts a mistrustful eye at a neighbor in the welfare office, and then passes into a sort of human fadeout (but to gray, rather than black) and then she starts offering a random chapter of fruity-voweled autobiography. "You see, I married rather beneath me...," she expounds, listing heavily to one side, as though her posture has aphasia; she is vehement in her pronunciations, as though she's a deaf old beast trying to hear herself but also as though she's taking patrician care in making her own life story, which is fascinating if she doesn't mind saying so, perfectly pellucid to other people. Few of these vocal, bodily, or attitudinal habits feel like anything I've seen before, and the enigmas or the brazenness or the stillness or the unexpectedness of each of them only lends more mystique to the others—but always with the effect of playing Mrs. Ross, not playing "mystique."

Evans clearly has a complex and practiced take on old age, and is interested in the atmospheric and psychological tensions generated by slowing things down. Mrs. Ross doesn't whip from reveries to indictments to fogginess to paralysis with Three Faces of Eve suddenness. She's not interested in putting on a light show. The effect is closer to that of a cloudy crystal ball, in which one side of this woman emerges for a moment before singing back into the whited-out mist, from which some other face emerges a beat or two later, and often quite a different one. Mrs. Ross lags into weary dumbfoundedness, staring at nothing and not moving for a few moments in a row, before leaping with sudden dispatch to pound her broomstick against her ceiling, in protest of the upstairs neighbors and their noisiness. She casts a mistrustful eye at a neighbor in the welfare office, and then passes into a sort of human fadeout (but to gray, rather than black) and then she starts offering a random chapter of fruity-voweled autobiography. "You see, I married rather beneath me...," she expounds, listing heavily to one side, as though her posture has aphasia; she is vehement in her pronunciations, as though she's a deaf old beast trying to hear herself but also as though she's taking patrician care in making her own life story, which is fascinating if she doesn't mind saying so, perfectly pellucid to other people. Few of these vocal, bodily, or attitudinal habits feel like anything I've seen before, and the enigmas or the brazenness or the stillness or the unexpectedness of each of them only lends more mystique to the others—but always with the effect of playing Mrs. Ross, not playing "mystique."

Woodward wears her character the way you wear a well-tailored leather glove. As in other roles, she is a consummate professional at eliminating almost any sense of space between herself and Rita, even though Rita clearly finds her own habits stifling and itchy at times (at other times, she's more than happy to flaunt them), and her affects must be slightly itchy for the actress to have to play. But hand Woodward a dislikable woman of a certain age, and she'll play dislikability like it's a prized viola. She comes across as a staunch, somewhat severe defender of her characters, partly for contextual reasons. That is, so few American actresses seem willing (or, to be fair, get asked) to play these sorts of women; "difficult" types in American movies are so often barnstorming crusaders in the Norma Rae vein, or comic villainesses, or harridans. Woodward was very rare, then, in establishing a métier in forms of everyday astringency, and not only refusing to dull these women's edges but actively working to sharpen them, the way a practiced cook takes care of her knives. What I find most remarkable about this is that Woodward's protectiveness toward the characters' refusals to be charmers or mannequins does not spill into a subtle PR campaign to get us unreservedly on their side. Rita is a pill with a point of view, but still a pill. Her ornery way of pointing out her daughter's self-involvement is not likely to prompt the girl toward newfound generosity, just as it's not clear who wins, including Rita, by being so very caustic at a family funeral, where her refusal to sell off the property of the deceased is no more or less reasonable than the eagerness of her relatives to get rid of the estate and divvy up the profits. A crevasse has opened between Rita and her offscreen gay son, who communicates only with his sister; given Woodward's talent at conveying deeper feelings inside an inflexible, almost cutting reserve, you don't need to meet this son to empathize with his decision to estrange himself, even though you can't write Rita off as a harpy or a bigot.

Woodward wears her character the way you wear a well-tailored leather glove. As in other roles, she is a consummate professional at eliminating almost any sense of space between herself and Rita, even though Rita clearly finds her own habits stifling and itchy at times (at other times, she's more than happy to flaunt them), and her affects must be slightly itchy for the actress to have to play. But hand Woodward a dislikable woman of a certain age, and she'll play dislikability like it's a prized viola. She comes across as a staunch, somewhat severe defender of her characters, partly for contextual reasons. That is, so few American actresses seem willing (or, to be fair, get asked) to play these sorts of women; "difficult" types in American movies are so often barnstorming crusaders in the Norma Rae vein, or comic villainesses, or harridans. Woodward was very rare, then, in establishing a métier in forms of everyday astringency, and not only refusing to dull these women's edges but actively working to sharpen them, the way a practiced cook takes care of her knives. What I find most remarkable about this is that Woodward's protectiveness toward the characters' refusals to be charmers or mannequins does not spill into a subtle PR campaign to get us unreservedly on their side. Rita is a pill with a point of view, but still a pill. Her ornery way of pointing out her daughter's self-involvement is not likely to prompt the girl toward newfound generosity, just as it's not clear who wins, including Rita, by being so very caustic at a family funeral, where her refusal to sell off the property of the deceased is no more or less reasonable than the eagerness of her relatives to get rid of the estate and divvy up the profits. A crevasse has opened between Rita and her offscreen gay son, who communicates only with his sister; given Woodward's talent at conveying deeper feelings inside an inflexible, almost cutting reserve, you don't need to meet this son to empathize with his decision to estrange himself, even though you can't write Rita off as a harpy or a bigot.

You can see why Greville is briefly moved, but even setting aside his cynical preoccupations—all he cares about is his precarious position as the likely heir to his unwed uncle, the famous Lord Hamilton—it's equally easy for the audience to relate to his rapid cooling of affection. Griffith is bubbly but rather free of personality, as though her top billing and the well-known real-life tale guarantee that anything she does will be received as impossibly enticing. I find her a bit fidgety, like Clara Bow having a go at one of Lillian Gish's true-heart Susies. When this mostly silent picture requires that she sing, Griffith is too stiff and arbitrary in her movements to communicate any musicality at all, much less any relation to the song we actually hear (even if, as is quite possible, this track was selected later). You'd have to be stonier than I am not to take pity on her as Greville sends her packing to Naples, especially since that's not the worst of it. He's assuming that her sparkling youth, matched with her social impossibility in every other respect (she's the cook's daughter!), will be enough to prompt his elderly uncle's infatuation while standing in the way of an actual marriage, thus preventing any biological sons from dislodging Greville's claim to Lord Hamilton's fortune and influence. We know all of this, while Emma knows none of it. What she renders, as a result, is a simple but plaintive impression of a broken-hearted teenager. I do wish, though, that Griffith had struggled a bit more with her feelings, or with such an open disclosure of them, and maybe that she ahd showed more of an intuitive hunch that Greville's motives are stained with greater sins than fickleness.

You can see why Greville is briefly moved, but even setting aside his cynical preoccupations—all he cares about is his precarious position as the likely heir to his unwed uncle, the famous Lord Hamilton—it's equally easy for the audience to relate to his rapid cooling of affection. Griffith is bubbly but rather free of personality, as though her top billing and the well-known real-life tale guarantee that anything she does will be received as impossibly enticing. I find her a bit fidgety, like Clara Bow having a go at one of Lillian Gish's true-heart Susies. When this mostly silent picture requires that she sing, Griffith is too stiff and arbitrary in her movements to communicate any musicality at all, much less any relation to the song we actually hear (even if, as is quite possible, this track was selected later). You'd have to be stonier than I am not to take pity on her as Greville sends her packing to Naples, especially since that's not the worst of it. He's assuming that her sparkling youth, matched with her social impossibility in every other respect (she's the cook's daughter!), will be enough to prompt his elderly uncle's infatuation while standing in the way of an actual marriage, thus preventing any biological sons from dislodging Greville's claim to Lord Hamilton's fortune and influence. We know all of this, while Emma knows none of it. What she renders, as a result, is a simple but plaintive impression of a broken-hearted teenager. I do wish, though, that Griffith had struggled a bit more with her feelings, or with such an open disclosure of them, and maybe that she ahd showed more of an intuitive hunch that Greville's motives are stained with greater sins than fickleness.

To no one's surprise, Gardner extends some automatic provisions to the film's exploration of eroticism. She makes an entrance showering behind a low bamboo wall, her bare shoulders nearly upstaged by her sexily insolent facial features. Watching her case out the grounds with the giraffes, the elephants, the leopards, the and rhinos is like seeing one exquisite, improbable specimen take a loping tour of fellow creatures that God designed while in the same buoyant, slightly absurd mood. Mercifully, Gardner doesn't gild the lily by doing anything to play "sexy" in these scenes; her figure and her costumes do that work for her. Her bigger accomplishment, the kind of thing that is perennially under-rewarded as good acting, lies in asserting her ease so quickly in what is nonetheless an uncomfortable locale. Neither in terms of her gender nor her carnality nor in any other respect does Gardner belabor Eloise's incongruity amid this scrappy, masculine, member's-only environment, even as the story and the direction take pivotal note of her flamboyant, temperature-shifting unexpectedness. All the guys around Gable, and eventually Victor himself, take a shine to the globetrotting gal as one of their own, not by any metaphorical association with her vocation but as people who don't require a lot of pillows or pretense. They're generally easygoing adults who know exactly who they are, despite their harsh, competitive, rough-and-tumble context. Leaning neither on an overdone masque of femininity nor on a strategic performance of "masculine" hardiness, gauging herself somewhere between a woman who's obviously out of her element and one who is pretty hard to unsettle, Gardner gives the movie swing, lightness, and personability, resisting all the typical routes for selling some generic persona of oneself to the audience or the other characters. She's witty, whipsmart, and confident of her attractiveness, but in a refreshingly rounded way that doesn't break a sweat flaunting any of those traits, or privileging one as her signal calling-card. She doesn't compete with Gable or with anyone to be the spitfire, the party-gal, or the wisely nurturing influence. She presumes her complementarity with him rather than figuring out how specifically to pitch it to him and to us, despite simultaneously suggesting that Eloise is more instantly drawn to Victor than he is to her.

To no one's surprise, Gardner extends some automatic provisions to the film's exploration of eroticism. She makes an entrance showering behind a low bamboo wall, her bare shoulders nearly upstaged by her sexily insolent facial features. Watching her case out the grounds with the giraffes, the elephants, the leopards, the and rhinos is like seeing one exquisite, improbable specimen take a loping tour of fellow creatures that God designed while in the same buoyant, slightly absurd mood. Mercifully, Gardner doesn't gild the lily by doing anything to play "sexy" in these scenes; her figure and her costumes do that work for her. Her bigger accomplishment, the kind of thing that is perennially under-rewarded as good acting, lies in asserting her ease so quickly in what is nonetheless an uncomfortable locale. Neither in terms of her gender nor her carnality nor in any other respect does Gardner belabor Eloise's incongruity amid this scrappy, masculine, member's-only environment, even as the story and the direction take pivotal note of her flamboyant, temperature-shifting unexpectedness. All the guys around Gable, and eventually Victor himself, take a shine to the globetrotting gal as one of their own, not by any metaphorical association with her vocation but as people who don't require a lot of pillows or pretense. They're generally easygoing adults who know exactly who they are, despite their harsh, competitive, rough-and-tumble context. Leaning neither on an overdone masque of femininity nor on a strategic performance of "masculine" hardiness, gauging herself somewhere between a woman who's obviously out of her element and one who is pretty hard to unsettle, Gardner gives the movie swing, lightness, and personability, resisting all the typical routes for selling some generic persona of oneself to the audience or the other characters. She's witty, whipsmart, and confident of her attractiveness, but in a refreshingly rounded way that doesn't break a sweat flaunting any of those traits, or privileging one as her signal calling-card. She doesn't compete with Gable or with anyone to be the spitfire, the party-gal, or the wisely nurturing influence. She presumes her complementarity with him rather than figuring out how specifically to pitch it to him and to us, despite simultaneously suggesting that Eloise is more instantly drawn to Victor than he is to her.

At present, Mrs. Hammond rents a room to another rising rugby phenom named Frank Machin (a hulking and excellent Richard Harris), and when she says she's only doing it for the money, we know she isn't making it up. Bent over a sewing machine, shooting off fuck-you glares while she makes the beds and brushes off Frank's tyro enthusiasm about his rise up through the ranks, Roberts's Margaret unquestionably feels that she's seen this all before: as an abandoned woman, as a wife who competed with the rival thrills of sport, as a toiler and saver in a highly class-stratified society where the working class oughtn't lie to themselves about their long- or even their short-term prospects. It's a brusquely pragmatic arrangement, and yet Mrs. Hammond does seem to study Frank as someone for whom she harbors both contempt and a grudging interest, as someone who might teach her something about the man she lost and/or pushed away, as someone whose own motivations for charming her children and begging romantic affection from her don't make immediate sense... though she may not be as dead-set against his hardbodied appeal as she thinks she is. And the prospect of more money—for all that she doubts whether Frank's burgeoning celebrity within the league will continue paying dividends or inspiring protectiveness from his owner-managers—cannot be lost on Margaret, either. She cracks one of many bitter jokes when Frank, after some nervy negotiation, returns to the flat with a kingly £1,000 paycheck. Shimmering with pride and excitement, he wants her to guess his worth before showing her the check. "Threepence?" she fires back, like a taut tripwire of emasculating blasts, yet her bolted-down frown does crack into its first smile as he divulges the actual fortune. Then again, it's only another moment before she reflects, spitefully, "It's a bit more than I got when my husband died... You didn't have to do anything for it... Some people have life made for them."

At present, Mrs. Hammond rents a room to another rising rugby phenom named Frank Machin (a hulking and excellent Richard Harris), and when she says she's only doing it for the money, we know she isn't making it up. Bent over a sewing machine, shooting off fuck-you glares while she makes the beds and brushes off Frank's tyro enthusiasm about his rise up through the ranks, Roberts's Margaret unquestionably feels that she's seen this all before: as an abandoned woman, as a wife who competed with the rival thrills of sport, as a toiler and saver in a highly class-stratified society where the working class oughtn't lie to themselves about their long- or even their short-term prospects. It's a brusquely pragmatic arrangement, and yet Mrs. Hammond does seem to study Frank as someone for whom she harbors both contempt and a grudging interest, as someone who might teach her something about the man she lost and/or pushed away, as someone whose own motivations for charming her children and begging romantic affection from her don't make immediate sense... though she may not be as dead-set against his hardbodied appeal as she thinks she is. And the prospect of more money—for all that she doubts whether Frank's burgeoning celebrity within the league will continue paying dividends or inspiring protectiveness from his owner-managers—cannot be lost on Margaret, either. She cracks one of many bitter jokes when Frank, after some nervy negotiation, returns to the flat with a kingly £1,000 paycheck. Shimmering with pride and excitement, he wants her to guess his worth before showing her the check. "Threepence?" she fires back, like a taut tripwire of emasculating blasts, yet her bolted-down frown does crack into its first smile as he divulges the actual fortune. Then again, it's only another moment before she reflects, spitefully, "It's a bit more than I got when my husband died... You didn't have to do anything for it... Some people have life made for them."