Picked Flick #84: Orlando

I, though, was secretly much more taken with Orlando, a movie I had virtually made up my mind to love anyway. Another anecdote: the first issue of Entertainment Weekly I ever bought and obsessed over was the Summer Movie Preview in 1993, warmly remembered for the moment at which I finished reading about Cliffhanger and Jurassic Park and Sleepless in Seattle and suddenly flipped to a picture of a red-headed androgyne and a withered old man cast as Queen Elizabeth, both of them bedecked in the most outlandishly plush theatrical finery while escorting a pack of grey, almost aqueline hunting dogs down the proverbial garden path. Aside from its sheer beauty, I couldn't believe that this picture was afforded a full half-page, or that the plot explored a literal, magical switching of a person's gender, or that it was written by this "Virginia Woolf" about whom I was just learning. (Albee's pun escaped me entirely; frankly, it kind of still does.) It was hard for me to imagine that Orlando could possibly measure up to the promise of this photostill, so imagine my awe when that shot came and went a mere 10 or 15 minutes into the film. Imagine my elation at actually loving the film, rather than just posing as one who loved it. The minute I reached the end of The Vampire Lestat, which I was then reading, I lept into Woolf's novel, was stunned by how different it was in tone as well as incident, but I loved it just as much, and couldn't stop gazing at Tilda Swinton's arch but somehow sly, Holbein-type portrait on the cover of the Harcourt Brace reprint. We could sum all of this up as a sort of Queen's Throat moment in a wee, proto-queer cinephile's young life, and for all of these reasons, Orlando will always remain a favorite.

I, though, was secretly much more taken with Orlando, a movie I had virtually made up my mind to love anyway. Another anecdote: the first issue of Entertainment Weekly I ever bought and obsessed over was the Summer Movie Preview in 1993, warmly remembered for the moment at which I finished reading about Cliffhanger and Jurassic Park and Sleepless in Seattle and suddenly flipped to a picture of a red-headed androgyne and a withered old man cast as Queen Elizabeth, both of them bedecked in the most outlandishly plush theatrical finery while escorting a pack of grey, almost aqueline hunting dogs down the proverbial garden path. Aside from its sheer beauty, I couldn't believe that this picture was afforded a full half-page, or that the plot explored a literal, magical switching of a person's gender, or that it was written by this "Virginia Woolf" about whom I was just learning. (Albee's pun escaped me entirely; frankly, it kind of still does.) It was hard for me to imagine that Orlando could possibly measure up to the promise of this photostill, so imagine my awe when that shot came and went a mere 10 or 15 minutes into the film. Imagine my elation at actually loving the film, rather than just posing as one who loved it. The minute I reached the end of The Vampire Lestat, which I was then reading, I lept into Woolf's novel, was stunned by how different it was in tone as well as incident, but I loved it just as much, and couldn't stop gazing at Tilda Swinton's arch but somehow sly, Holbein-type portrait on the cover of the Harcourt Brace reprint. We could sum all of this up as a sort of Queen's Throat moment in a wee, proto-queer cinephile's young life, and for all of these reasons, Orlando will always remain a favorite.There are other reasons, Swinton's gorgeous and utterly impossible face being one. Watching Young Adam last year with a friend, I leaned into his ear and said, "Her face is like a brain." You can literally read her thoughts, in an almost disconcertingly subtle and complete way, and the thoughts are always interesting—sometimes much more so than the movies she's in, though that isn't the case with Orlando. Released as Derek Jarman lay dying, though of course I had no sense of this at the time, Orlando confirmed that both Swinton and costume designer/archangel Sandy Powell would have thriving careers even without their patron and discoverer. I like to think of the frankly wobbly coda of Orlando, when Sally Potter uses rough, handheld Super 8 to render the modern Orlando's return to the field where we first met him/her, as at least in part a gentle elegy for Jarman, who so brilliantly pioneered the interpolation of celluloid and video as a uniquely expressive collage-form for the cinema. I like how many of Orlando's technical ventures pay off, like David Motion's defiantly modern score, as brazenly instrumented as those of Jon Brion but with techno undercurrents and, still yet, some classical melodic lines. I like the use of Russian and Uzbek locations to sub in for, respectively, the dowager Elizabeth's icebound Winter Court and the blistering palace-resort of Lothaire Bluteau's Turkish pasha, and I like wondering how they possibly made this movie for $5 million. I like that cinematographer Alexei Rodionov's mannerist motif of panning back and forth between dialogue speakers, bending if not quite breaking ye olde 180° rule, somehow resonates as clever rather than just as a sterile conceit in this story all about cryptic transitions and spaces between. The later epochs in the narrative get something of a bum's rush after all the visual, musical, and narrative lavishments on the early passages, but Orlando is a hoot, a hit, and a surprisingly boisterous comedy for most of its running time. You'd expect it to smell like scholarly folios, but it doesn't. It's as warm as those morning rays of sun that discover before anyone else does, with no Crying Game anxieties whatsoever, that he isn't a he anymore. (Click here for the full list of Nick's Picked Flicks.)

Labels: 1990s, Favorites, Literature, Queer Cinema, Tilda Swinton, Virginia Woolf

Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

As the handful of votes straggled in for the Picked Flicks Poll for #91-100, I inititally suspected

As the handful of votes straggled in for the Picked Flicks Poll for #91-100, I inititally suspected

Extending the happy coincidences, we begin with Lisa Cholodenko's High Art, which itself commences in a literal meditation on how women look—a double-entendre that, like "high art" itself, is fully and richly intentional. During the opening credits sequence, dotted with the names of female actors, editors, cinematographers, costume designers, producers and executive producers, and writer-director Cholodenko, Radha Mithcell's Syd pores over a handful of photographic slides at her light-table. The camera is entranced by her searching, intelligent eyes, starkly framed in thick black glasses, rather than by her body or by the objects at which she gazes. Within the same sequence, though, this isolated woman makes her way home through an empty office building and an uninhabited subway station, all shot from the kinds of oblique angles and the dusky, doomy shadows that tend to signal female victimization in all ranges of popular cinema. The movie prowls somewhere in the spectrum between Screen, the journal, and Scream, the girls-in-peril franchise, and that's hardly the last spectrum whose measure High Art will take. Between still photos and the moving image, between gay and straight, ambition and love, addiction and lucidity, there is sometimes a wide and nervy chasm in this movie, and at other moments nothing more than a pause, a comma, a slide over to the next seat on the couch. As the plot unfolds, High Art's debts to All About Eve become clearer, duplicating the essential scenarios of cunning, camaraderie, idol-slaying, and creative power even as it lures into the light the earlier film's lesbian undertows.

Extending the happy coincidences, we begin with Lisa Cholodenko's High Art, which itself commences in a literal meditation on how women look—a double-entendre that, like "high art" itself, is fully and richly intentional. During the opening credits sequence, dotted with the names of female actors, editors, cinematographers, costume designers, producers and executive producers, and writer-director Cholodenko, Radha Mithcell's Syd pores over a handful of photographic slides at her light-table. The camera is entranced by her searching, intelligent eyes, starkly framed in thick black glasses, rather than by her body or by the objects at which she gazes. Within the same sequence, though, this isolated woman makes her way home through an empty office building and an uninhabited subway station, all shot from the kinds of oblique angles and the dusky, doomy shadows that tend to signal female victimization in all ranges of popular cinema. The movie prowls somewhere in the spectrum between Screen, the journal, and Scream, the girls-in-peril franchise, and that's hardly the last spectrum whose measure High Art will take. Between still photos and the moving image, between gay and straight, ambition and love, addiction and lucidity, there is sometimes a wide and nervy chasm in this movie, and at other moments nothing more than a pause, a comma, a slide over to the next seat on the couch. As the plot unfolds, High Art's debts to All About Eve become clearer, duplicating the essential scenarios of cunning, camaraderie, idol-slaying, and creative power even as it lures into the light the earlier film's lesbian undertows. The sweet-temperedness of Where Is the Friend's Home? is a main reason why the film appeals so profoundly, and why it helped to jumpstart the international zeitgeist of enthusiasm for Iranian cinema. Especially by comparison to the rigid conceptions of Kiarostami's recent work, the film is unabashedly rooted in human sympathy, an affecting but never cloying scenario, and a neorealist filming style to make Bazin cheer from the grave. Kiarostami carefully but unobtrusively manages the frame even while tracking young Ahmed through the sidewinding paths and chutes of Poshteh, so that our own visual sense unites permanent dislocation with the constant unfolding of discovery. (

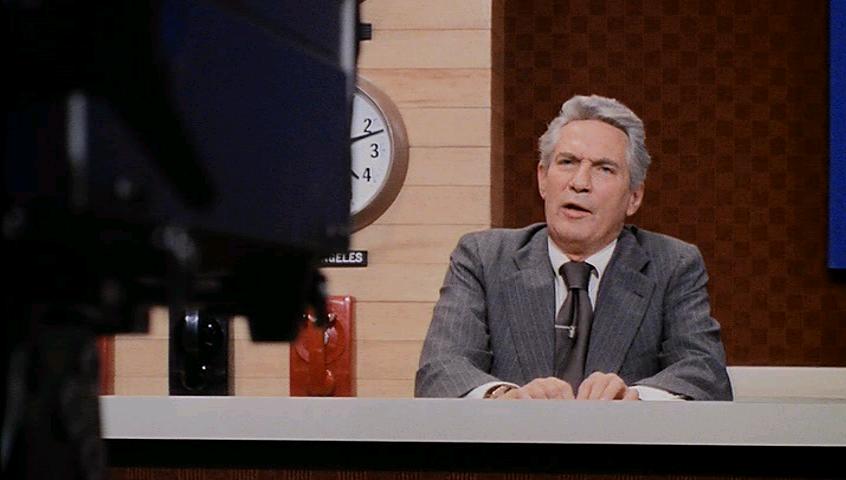

The sweet-temperedness of Where Is the Friend's Home? is a main reason why the film appeals so profoundly, and why it helped to jumpstart the international zeitgeist of enthusiasm for Iranian cinema. Especially by comparison to the rigid conceptions of Kiarostami's recent work, the film is unabashedly rooted in human sympathy, an affecting but never cloying scenario, and a neorealist filming style to make Bazin cheer from the grave. Kiarostami carefully but unobtrusively manages the frame even while tracking young Ahmed through the sidewinding paths and chutes of Poshteh, so that our own visual sense unites permanent dislocation with the constant unfolding of discovery. ( Network wastes no time barreling right into its scabrous satire of an abscessed national media, of middle-age panic and youthful zealotry, of sensational diversions that conceal the corporate racket, of how a graduated mid-life apoplexy, perhaps outright insanity, nonetheless passes for messianic enlightenment in a world that's this far gone. Network remains prescient, urgent, hilarious, and relevant today, almost 30 years after its debut, and it's of course profoundly sad that this is the case. It's easy to lament the fact that post-Y2K television has promulgated so many programs that would have slid quite nicely into the deranged rubric of The Howard Beale Show. Bill O'Reilly is scantily less crazy than Howard Beale, speaking only of his contempt for corroborated fact and his perpetual state of spoiled-child ire, not about his politics. The endless procession of Survivors and Idols and Models and Millionaires are even more vapid than Sybil the Soothsayer, the rumored but never-heard Vox Populi, and other Guignol series and spinoffs that Chayefsky devises for his fictional UBS. More harrowing is the fact that Network actually strikes much closer to the angry red iron of what's really going wrong—the transnational corporations duping their own senior staffs and worshipping the dollar in a quite literal way—than do the endless contemporary editorials about the atrophied content of today's TV. Content is just a symptom. As Faye Dunaway's brazenly cloven-hoofed Diana Christensen yells at a Marxist, terrorist-affiliated demagogue-for-hire, "I don't give a damn about the political content of the show!" So little damns are given in this movie, I feel sure I'd have spotted one, had the occasion ever arisen.

Network wastes no time barreling right into its scabrous satire of an abscessed national media, of middle-age panic and youthful zealotry, of sensational diversions that conceal the corporate racket, of how a graduated mid-life apoplexy, perhaps outright insanity, nonetheless passes for messianic enlightenment in a world that's this far gone. Network remains prescient, urgent, hilarious, and relevant today, almost 30 years after its debut, and it's of course profoundly sad that this is the case. It's easy to lament the fact that post-Y2K television has promulgated so many programs that would have slid quite nicely into the deranged rubric of The Howard Beale Show. Bill O'Reilly is scantily less crazy than Howard Beale, speaking only of his contempt for corroborated fact and his perpetual state of spoiled-child ire, not about his politics. The endless procession of Survivors and Idols and Models and Millionaires are even more vapid than Sybil the Soothsayer, the rumored but never-heard Vox Populi, and other Guignol series and spinoffs that Chayefsky devises for his fictional UBS. More harrowing is the fact that Network actually strikes much closer to the angry red iron of what's really going wrong—the transnational corporations duping their own senior staffs and worshipping the dollar in a quite literal way—than do the endless contemporary editorials about the atrophied content of today's TV. Content is just a symptom. As Faye Dunaway's brazenly cloven-hoofed Diana Christensen yells at a Marxist, terrorist-affiliated demagogue-for-hire, "I don't give a damn about the political content of the show!" So little damns are given in this movie, I feel sure I'd have spotted one, had the occasion ever arisen. Even more than the justly famous

Even more than the justly famous

With the possible exception of

With the possible exception of  Another of the funniest bits, though heartbreaking in context, is "I - was so - hungry! I was starving!!" Margaret lets fly with that curveball at the point in her live, one-woman show when she has stopped (well, mostly stopped) explicitly catering to her hometown and way-gay San Francisco audience and is chronicling her own short, unhappy life as a corporate-fabricated Asian-American poster child in the mid-1990s. Cast in an "Asian family" sitcom whose cast of characters were all, to anyone paying attention, of completely different Asian ethnicities. Coercively shadowed by an "Asian advisor" who would dog her around the set and teach her to be "more" Asian. ("Here, use these chopsticks!" Cho ventriloquizes in wicked but pained memory, "and then, you can put them in your hair!") All the while, Cho was fighting dietary dictates from the network and the eating disorders they inevitably provoked, as well as various addictions, sexual recklessness and eventual victimization, crushed expectations, vicious "fanmail," industry racism, and everything else under the Angelino sun. As she tells the story, with no matter how much foul-mouthed and knee-slapping wit, you can see that she's beating back every ghost in the book. Maybe this time, she'll win.

Another of the funniest bits, though heartbreaking in context, is "I - was so - hungry! I was starving!!" Margaret lets fly with that curveball at the point in her live, one-woman show when she has stopped (well, mostly stopped) explicitly catering to her hometown and way-gay San Francisco audience and is chronicling her own short, unhappy life as a corporate-fabricated Asian-American poster child in the mid-1990s. Cast in an "Asian family" sitcom whose cast of characters were all, to anyone paying attention, of completely different Asian ethnicities. Coercively shadowed by an "Asian advisor" who would dog her around the set and teach her to be "more" Asian. ("Here, use these chopsticks!" Cho ventriloquizes in wicked but pained memory, "and then, you can put them in your hair!") All the while, Cho was fighting dietary dictates from the network and the eating disorders they inevitably provoked, as well as various addictions, sexual recklessness and eventual victimization, crushed expectations, vicious "fanmail," industry racism, and everything else under the Angelino sun. As she tells the story, with no matter how much foul-mouthed and knee-slapping wit, you can see that she's beating back every ghost in the book. Maybe this time, she'll win. Having already announced the opening decalogue of the

Having already announced the opening decalogue of the  Meanwhile, I thought it would be fun (hey, it's fun for me!) to give a quick decade-by-decade rundown of the films that almost made the list but didn't quite, all of which you should absolutely rent, and all of which were anguishing to leave off:

Meanwhile, I thought it would be fun (hey, it's fun for me!) to give a quick decade-by-decade rundown of the films that almost made the list but didn't quite, all of which you should absolutely rent, and all of which were anguishing to leave off: Finally, before you all lose total patience with this entry, this obsession, this blog, this person, I really have to encourage you to pore over

Finally, before you all lose total patience with this entry, this obsession, this blog, this person, I really have to encourage you to pore over  Djibril Diop Mambéty's funny, harrowing, colorful, and terrifically astute Hyenas is an emblematic case of a masterpiece—and a good time at the movies, to boot—that these cultural trends wholly short-change. Heroically, it did participate in the Cannes competition lineup in 1992 and in that year's New York Film Festival, it was micro-mini released in commercial venues that fall, and it's available for rent on DVD or VHS. So, hop on it, and observe how piquantly Mambéty adapts Friedrich Dürrenmatt's The Visit, one of the twentieth century's great plays, and infuses the material with exciting, entertaining, and shrewd new meanings within the West African context. The plot concerns how Linguère Ramatou, an acerbic, broken-bodied, and vengeful old woman, returns to her small-town hamlet after decades of amassing a shadowy fortune. She now indulges the citizens with improbable luxuries and other, decadent incentives so long as they agree to execute the town's most popular citizen—in this version, an avuncular barkeep and shopowner named Draman Drameh, who long ago denied having fathered the illegitimate child that occasioned Linguère's banishment in the first place. The bankrupt village, whose town hall is impounded in a very early sequence, has a peculiarly African (but also not peculiarly African) susceptibility to superficial remedies and cults of personality, and they are sure that the woman's promised fortune shall be their redemption, even as they profess outrage at the demand for Draman Drameh's head... and even as Linguère and Draman volley back and forth between nostalgic recollections of their ancient affair and bitter disputes over her grudge and its consequences.

Djibril Diop Mambéty's funny, harrowing, colorful, and terrifically astute Hyenas is an emblematic case of a masterpiece—and a good time at the movies, to boot—that these cultural trends wholly short-change. Heroically, it did participate in the Cannes competition lineup in 1992 and in that year's New York Film Festival, it was micro-mini released in commercial venues that fall, and it's available for rent on DVD or VHS. So, hop on it, and observe how piquantly Mambéty adapts Friedrich Dürrenmatt's The Visit, one of the twentieth century's great plays, and infuses the material with exciting, entertaining, and shrewd new meanings within the West African context. The plot concerns how Linguère Ramatou, an acerbic, broken-bodied, and vengeful old woman, returns to her small-town hamlet after decades of amassing a shadowy fortune. She now indulges the citizens with improbable luxuries and other, decadent incentives so long as they agree to execute the town's most popular citizen—in this version, an avuncular barkeep and shopowner named Draman Drameh, who long ago denied having fathered the illegitimate child that occasioned Linguère's banishment in the first place. The bankrupt village, whose town hall is impounded in a very early sequence, has a peculiarly African (but also not peculiarly African) susceptibility to superficial remedies and cults of personality, and they are sure that the woman's promised fortune shall be their redemption, even as they profess outrage at the demand for Draman Drameh's head... and even as Linguère and Draman volley back and forth between nostalgic recollections of their ancient affair and bitter disputes over her grudge and its consequences. Adapted from a novel by Booth Tarkington—the writer, too, of The Magnificent Ambersons—Alice Adams tells the story of a lower-middle-class girl, not far past her schooling years, who positively quivers with longing to join the coterie of her more fashionable peers and to find the kind of domestic bliss that presumably once united her parents (the excellent Fred Stone and Ann Shoemaker), whose tacit bond of affection is now sorely tested by illness, monetary need, and other trials of late middle-age. Alice Adams is the kind of girl who would adore Pride and Prejudice, even though in real life she might well have settled for Mr. Collins. One of the major ambitions of the screenplay and, I'm guessing, the novel is to keep Alice so dotingly loyal to her family even as she dreams of something bigger or other than what they have, which often compels a shame of her circumstances and a coy dishonesty about who she is and who they are. That the emblematically patrician Hepburn is so convincing within both this cast and this caste is a complete revelation, even more so in hindsight than it must have been in 1935, but her empathetic connection to this girl's gossamer aspirations couldn't be clearer. Her body and voice are much more relaxed than we're used to seeing and hearing them, and even though she takes center stage in a way she wouldn't truly do again until David Lean's Summertime in 1955, she holds the movie, as she does the character, with graceful, unpugnacious care, as though cupping her hand around the spores of a dandelion, keeping them from blowing away.

Adapted from a novel by Booth Tarkington—the writer, too, of The Magnificent Ambersons—Alice Adams tells the story of a lower-middle-class girl, not far past her schooling years, who positively quivers with longing to join the coterie of her more fashionable peers and to find the kind of domestic bliss that presumably once united her parents (the excellent Fred Stone and Ann Shoemaker), whose tacit bond of affection is now sorely tested by illness, monetary need, and other trials of late middle-age. Alice Adams is the kind of girl who would adore Pride and Prejudice, even though in real life she might well have settled for Mr. Collins. One of the major ambitions of the screenplay and, I'm guessing, the novel is to keep Alice so dotingly loyal to her family even as she dreams of something bigger or other than what they have, which often compels a shame of her circumstances and a coy dishonesty about who she is and who they are. That the emblematically patrician Hepburn is so convincing within both this cast and this caste is a complete revelation, even more so in hindsight than it must have been in 1935, but her empathetic connection to this girl's gossamer aspirations couldn't be clearer. Her body and voice are much more relaxed than we're used to seeing and hearing them, and even though she takes center stage in a way she wouldn't truly do again until David Lean's Summertime in 1955, she holds the movie, as she does the character, with graceful, unpugnacious care, as though cupping her hand around the spores of a dandelion, keeping them from blowing away.

I know, I know, this movie came out, like, five minutes ago, but I ♥ Huckabees was the only movie of 2004 that I paid to see three times in a theater, and every time, I laughed like I was screaming. Every time, the triple-threat of Wahlberg, Hoffman, and Law proved that they deserved an Oscar category all their own for Flawless Comic Support Without Scenery-Hogging. Every time, the movie's sharp harpoons into the absurd fractiousness of the American "liberal" left hit all of their marks, even as the movie tipped all the sacred cows of big business, "Christian" hypocrisy, and star-studded realpolitik with equal aplomb. The movie is crazily deep with subtle touches, golden scenes, and brilliant sidebar performances. That dinner scene with Jean Smart and Richard Jenkins? The priceless walk-on from Talia Shire? Lily Tomlin, her desk strewn with notebooks titled "Coincidences" and "Galaxies" and "Fathers," refocusing her eyes every few seconds? Jon Brion's miraculous score, with the drunken calliope and the galloping rhythm? I ♥ed the whole thing, and I'm not seeing the love dissipating any time soon. (Click

I know, I know, this movie came out, like, five minutes ago, but I ♥ Huckabees was the only movie of 2004 that I paid to see three times in a theater, and every time, I laughed like I was screaming. Every time, the triple-threat of Wahlberg, Hoffman, and Law proved that they deserved an Oscar category all their own for Flawless Comic Support Without Scenery-Hogging. Every time, the movie's sharp harpoons into the absurd fractiousness of the American "liberal" left hit all of their marks, even as the movie tipped all the sacred cows of big business, "Christian" hypocrisy, and star-studded realpolitik with equal aplomb. The movie is crazily deep with subtle touches, golden scenes, and brilliant sidebar performances. That dinner scene with Jean Smart and Richard Jenkins? The priceless walk-on from Talia Shire? Lily Tomlin, her desk strewn with notebooks titled "Coincidences" and "Galaxies" and "Fathers," refocusing her eyes every few seconds? Jon Brion's miraculous score, with the drunken calliope and the galloping rhythm? I ♥ed the whole thing, and I'm not seeing the love dissipating any time soon. (Click  First

First  Maybe I love Cemetery Man because it's one of the few cult films in existence whose cult I blithely stumbled into, without even knowing it existed. Somehow, people everywhere seem to have seen this movie, which I caught on late-night Cinemax, O whorish bride of cable TV, one time when I was house-sitting. Everything that happens early in Cemetery Man happens again at least a dozen more times. Zombies, for the entertainment gods are good, can't stop rising out of the ground, seven days after their initial burial. Rupert, for every other kind of god is good, can't stop taking showers. That killer musical score, all sawing cellos and violins and deep-thrumming basses, never wears out its considerable welcome. The indecently buxom Italian sexpot who turns Rupert's eye, played by an actress called Anna Falchi, keeps dying and resurrecting herself, eventually returning in the guises of wholly different women, all with the same smutty expression. The mayor's daughter gets her head lopped off in a road accident, but when it comes back to life on its own, Rupert's porcine assistant has the politesse to perch it in the skeleton of a burned-out TV. Haven't you ever wanted to look out from the boob-tube instead of in? And did I mention this is played for laughs?

Maybe I love Cemetery Man because it's one of the few cult films in existence whose cult I blithely stumbled into, without even knowing it existed. Somehow, people everywhere seem to have seen this movie, which I caught on late-night Cinemax, O whorish bride of cable TV, one time when I was house-sitting. Everything that happens early in Cemetery Man happens again at least a dozen more times. Zombies, for the entertainment gods are good, can't stop rising out of the ground, seven days after their initial burial. Rupert, for every other kind of god is good, can't stop taking showers. That killer musical score, all sawing cellos and violins and deep-thrumming basses, never wears out its considerable welcome. The indecently buxom Italian sexpot who turns Rupert's eye, played by an actress called Anna Falchi, keeps dying and resurrecting herself, eventually returning in the guises of wholly different women, all with the same smutty expression. The mayor's daughter gets her head lopped off in a road accident, but when it comes back to life on its own, Rupert's porcine assistant has the politesse to perch it in the skeleton of a burned-out TV. Haven't you ever wanted to look out from the boob-tube instead of in? And did I mention this is played for laughs? There is much that is fascinating about Possessed, including the way it refuses to be written off as a crappy movie, even when the plot takes its serial nose-dives into purple implausibility, even when Franz Waxman indulges the most apoplectic arpeggios and electric-organ decrescendoes in the certifiably insane score. However ancient its notions of science—the title comes from Dr. Harvey Willard's expert opinion that Louise's schizoid persecution complex is one of many mental-health states that amounts to being "possessed by devils"—there's a feral, almost involuntary conviction to the film's interest in psychic unease that you don't really find in The Snake Pit or The Three Faces of Eve or other, comparable voyages into the classical Hollywood booby-hatch. The form of the film convulses amidst its own insensible agonies, alternating amongst elegant lakeside establishing shots, harshly expressionist chiaroscuro effects, uneasy dissolves, and at least one handheld tracking shot from the point of view of a dead woman who may or may not be haunting Louise (who, in turn, may or may not have killed this woman). It's easy to cackle and shrug at Warner Bros. potboilers like this, and Possessed repeatedly earns the cackliest cackle you can manage: it's that crazy, and that much fun. But it also feels symptomatic of...something, and harshly sincere: the sour force of spurned passion and the suffocating pressure of obsessive lovers who won't go away have rarely been given such free rein. The violence they exact on the movie's formal discipline is a major part of why you remember the picture.

There is much that is fascinating about Possessed, including the way it refuses to be written off as a crappy movie, even when the plot takes its serial nose-dives into purple implausibility, even when Franz Waxman indulges the most apoplectic arpeggios and electric-organ decrescendoes in the certifiably insane score. However ancient its notions of science—the title comes from Dr. Harvey Willard's expert opinion that Louise's schizoid persecution complex is one of many mental-health states that amounts to being "possessed by devils"—there's a feral, almost involuntary conviction to the film's interest in psychic unease that you don't really find in The Snake Pit or The Three Faces of Eve or other, comparable voyages into the classical Hollywood booby-hatch. The form of the film convulses amidst its own insensible agonies, alternating amongst elegant lakeside establishing shots, harshly expressionist chiaroscuro effects, uneasy dissolves, and at least one handheld tracking shot from the point of view of a dead woman who may or may not be haunting Louise (who, in turn, may or may not have killed this woman). It's easy to cackle and shrug at Warner Bros. potboilers like this, and Possessed repeatedly earns the cackliest cackle you can manage: it's that crazy, and that much fun. But it also feels symptomatic of...something, and harshly sincere: the sour force of spurned passion and the suffocating pressure of obsessive lovers who won't go away have rarely been given such free rein. The violence they exact on the movie's formal discipline is a major part of why you remember the picture. It's no wonder that Masked and Anonymous—whose title proudly proclaims its refusal to be known—isn't everyone's cup of tea. For what it's worth, I personally can't get enough of the way it plays such a mean game of three-card monte with our expectations and even our recognition of what we're watching: is Dylan "playing himself" or playing some alternative jam-meditation on the theme of himself? Is it okay to take seriously the movie's ramshackle vision of a tumbledown, Third World America, even as the major characters appear to joke and smirk about it? What do we make of the way that the screenplay's wry, aphoristic dialogue and allegorical figures hail straight from the lexicon of Dylan's own songwriting, and yet, minus the reassurances of melody and reputation, these same aesthetics feel even more inscrutable than usual? And does that make it easy not to respond to the roustabout humor that is all over Masked and Anonymous, fighting a worthy duel with the heartbroken sadness and the confessions of failure that infuse so many of its scenes? Are the actors in the movie simply flailing about without a flight manual, or is the free-verse, improvisatory style of these performances—beyond the immediate pleasures in turns as witty as Lange's or as crafty as Bridges'—germane to the message the movie is trying to convey? And what is that message, or is there no message? On the largest scale, I'd stick my neck out to say that Masked and Anonymous is a bright but scathing future-vision of the United States after only a few more years of the entertainment industry's profit-mongering and empty self-congratulations, not to mention of the impotence of modern liberalism and the factionalizing effects of a hubristic, hawkish, but increasingly shaky government. (In its tacit way, it's also one of the few American movies to presage a future of the country where Latino and Hispanic cultures come to permeate all levels of society, culture, and public provenance.) On the narrowest level, Dylan offers a kind of perversely private apologia for his own lapses as an artist and a man—which, the film seems well aware, is not fundamentally distinct from the other narcissistic enterprises that are suffocating the power of art even as, in many cases, they provide its steadiest fuel. No coward from paradox, this film.

It's no wonder that Masked and Anonymous—whose title proudly proclaims its refusal to be known—isn't everyone's cup of tea. For what it's worth, I personally can't get enough of the way it plays such a mean game of three-card monte with our expectations and even our recognition of what we're watching: is Dylan "playing himself" or playing some alternative jam-meditation on the theme of himself? Is it okay to take seriously the movie's ramshackle vision of a tumbledown, Third World America, even as the major characters appear to joke and smirk about it? What do we make of the way that the screenplay's wry, aphoristic dialogue and allegorical figures hail straight from the lexicon of Dylan's own songwriting, and yet, minus the reassurances of melody and reputation, these same aesthetics feel even more inscrutable than usual? And does that make it easy not to respond to the roustabout humor that is all over Masked and Anonymous, fighting a worthy duel with the heartbroken sadness and the confessions of failure that infuse so many of its scenes? Are the actors in the movie simply flailing about without a flight manual, or is the free-verse, improvisatory style of these performances—beyond the immediate pleasures in turns as witty as Lange's or as crafty as Bridges'—germane to the message the movie is trying to convey? And what is that message, or is there no message? On the largest scale, I'd stick my neck out to say that Masked and Anonymous is a bright but scathing future-vision of the United States after only a few more years of the entertainment industry's profit-mongering and empty self-congratulations, not to mention of the impotence of modern liberalism and the factionalizing effects of a hubristic, hawkish, but increasingly shaky government. (In its tacit way, it's also one of the few American movies to presage a future of the country where Latino and Hispanic cultures come to permeate all levels of society, culture, and public provenance.) On the narrowest level, Dylan offers a kind of perversely private apologia for his own lapses as an artist and a man—which, the film seems well aware, is not fundamentally distinct from the other narcissistic enterprises that are suffocating the power of art even as, in many cases, they provide its steadiest fuel. No coward from paradox, this film. Perhaps the film's supreme accomplishment is one of its simplest: the faith and good sense that have directed Green and his collaborators to film characters, scenes, relationships, and locations that simply never arise in American films, even, for the most part, movies as off the beaten path as this one. The commencing scene, in which the emotionally precocious 12-year-old Nasia breaks up with her 13-year-old, bespectacled boyfriend Buddy (Curtis Cotton III) is both jarring and heartwarming in its lack of irony. Beyond the fact that George Washington affords such generous time and space to pre-teen emotions, and beyond the extreme rarity of seeing African-American characters of any age depicted so warmly and lit so well in an American movie, the film really hits its stride when the young characters start criss-crossing with their elders, when the white kids and black kids reveal cliques and alliances that are just as mundane to them as they are surprising within our gentrified and color-lined national cinema. The only attributes that George Washington's characters share in common are the rural, weedy county they inhabit and their unenviable class position, which seems to account for why workplaces and domestic spaces blur into each other so imperceptibly, and why everyone seems to know each other so well (kids and adults, even relative strangers, all address each other easily by first name).

Perhaps the film's supreme accomplishment is one of its simplest: the faith and good sense that have directed Green and his collaborators to film characters, scenes, relationships, and locations that simply never arise in American films, even, for the most part, movies as off the beaten path as this one. The commencing scene, in which the emotionally precocious 12-year-old Nasia breaks up with her 13-year-old, bespectacled boyfriend Buddy (Curtis Cotton III) is both jarring and heartwarming in its lack of irony. Beyond the fact that George Washington affords such generous time and space to pre-teen emotions, and beyond the extreme rarity of seeing African-American characters of any age depicted so warmly and lit so well in an American movie, the film really hits its stride when the young characters start criss-crossing with their elders, when the white kids and black kids reveal cliques and alliances that are just as mundane to them as they are surprising within our gentrified and color-lined national cinema. The only attributes that George Washington's characters share in common are the rural, weedy county they inhabit and their unenviable class position, which seems to account for why workplaces and domestic spaces blur into each other so imperceptibly, and why everyone seems to know each other so well (kids and adults, even relative strangers, all address each other easily by first name). Brother's Keeper is not a perfect documentary by any means. Berlinger and Sinofsky, as in Paradise Lost, are perhaps artificial in streamlining their complex scenario into gothic-thriller dimensions, after which they follow the reverse instinct of playing all too obviously into the side of the case they prefer. Nonetheless, Brother's Keeper is a pretty extraordinary document, not least because the surviving Ward brothers are such craggy, enigmatic, and fascinating subjects for the cameramen, who at least have the grace not to leer at them outright. Shuffling about at the pace of Galapagos turtles, and marked by the same habit of palpably retreating into their private shells, the Wards do not quite seem to fit the visions of the prosecution, but nor do they seem well-suited to the "local hero" status they acquire from a roused local populace who smell a legal feeding frenzy and are determined to safeguard this trio of virtual hermits. An extremely strange social dynamic emerges, one that confers poetic justification on the name "Ward," though the film's intimate tracing of their existence cannot disguise the fact that nobody, filmmakers included, seems to know quite what to make of them. Too, the possibility subsists throughout that the Wards know more than they ever tell, and despite sensationalist undertows, the film never succumbs to romanticizing their silence. While watching other documentaries, not to mention while living as their regional neighbors in upstate New York, I have often thought of the Wards and their appalling poverty, their almost total privacy, and afterward their vulnerability to legal and finally artistic forms of surveillance which they must never have envisioned. Formally steadier than Capturing the Friedmans and less grandiose in the scope of what it imagines, Brother's Keeper won a slew of prizes from critics' groups when it was released, but it deserves a bigger following. (Click

Brother's Keeper is not a perfect documentary by any means. Berlinger and Sinofsky, as in Paradise Lost, are perhaps artificial in streamlining their complex scenario into gothic-thriller dimensions, after which they follow the reverse instinct of playing all too obviously into the side of the case they prefer. Nonetheless, Brother's Keeper is a pretty extraordinary document, not least because the surviving Ward brothers are such craggy, enigmatic, and fascinating subjects for the cameramen, who at least have the grace not to leer at them outright. Shuffling about at the pace of Galapagos turtles, and marked by the same habit of palpably retreating into their private shells, the Wards do not quite seem to fit the visions of the prosecution, but nor do they seem well-suited to the "local hero" status they acquire from a roused local populace who smell a legal feeding frenzy and are determined to safeguard this trio of virtual hermits. An extremely strange social dynamic emerges, one that confers poetic justification on the name "Ward," though the film's intimate tracing of their existence cannot disguise the fact that nobody, filmmakers included, seems to know quite what to make of them. Too, the possibility subsists throughout that the Wards know more than they ever tell, and despite sensationalist undertows, the film never succumbs to romanticizing their silence. While watching other documentaries, not to mention while living as their regional neighbors in upstate New York, I have often thought of the Wards and their appalling poverty, their almost total privacy, and afterward their vulnerability to legal and finally artistic forms of surveillance which they must never have envisioned. Formally steadier than Capturing the Friedmans and less grandiose in the scope of what it imagines, Brother's Keeper won a slew of prizes from critics' groups when it was released, but it deserves a bigger following. (Click

Restoring a little balance of power to the universe, and knocking me right off of The Piano Teacher's high-art pedestal, here are the two films from the John Hughes factory that double-double my refreshment every time I pull them off the shelf. I find it impossible to choose between The Breakfast Club, which Hughes directed from his own script, and Pretty in Pink, helmed by the otherwise dubious Howard Deutch. I saw The Breakfast Club when you're really supposed to, i.e., when you are roughly the same age or, better, just barely younger than the characters in the movie—from which vantage Hughes' empathetic grasp of high-school anhedonia is all the more rewarding and exciting, and also nicely tempered by a fair grasp of each character's naïveté and inadequacy. Gorgeously, and infectiously, the movie finds all of its adolescent leads in a gently embellished free-zone between the mess that real people are in high school and the stabler, frankly nicer people that Andy and Claire and Bender and the rest will palpably become later in their lives, given just a little bit of breathing-room to grow up and get over themselves. That said, I sure hope that Ally Sheedy's Allison, by far my favorite character, will forever continue to make her dandruff-derived objets and her all-carbs all-the-time sandwiches. Also priceless: Anthony Michael Hall's shambling diffidence, so hard-fought but so hilariously ill-concealed, and Judd Nelson's marvleous line reading of the single word "Claire," turning the name into some sort of insolent question.

Restoring a little balance of power to the universe, and knocking me right off of The Piano Teacher's high-art pedestal, here are the two films from the John Hughes factory that double-double my refreshment every time I pull them off the shelf. I find it impossible to choose between The Breakfast Club, which Hughes directed from his own script, and Pretty in Pink, helmed by the otherwise dubious Howard Deutch. I saw The Breakfast Club when you're really supposed to, i.e., when you are roughly the same age or, better, just barely younger than the characters in the movie—from which vantage Hughes' empathetic grasp of high-school anhedonia is all the more rewarding and exciting, and also nicely tempered by a fair grasp of each character's naïveté and inadequacy. Gorgeously, and infectiously, the movie finds all of its adolescent leads in a gently embellished free-zone between the mess that real people are in high school and the stabler, frankly nicer people that Andy and Claire and Bender and the rest will palpably become later in their lives, given just a little bit of breathing-room to grow up and get over themselves. That said, I sure hope that Ally Sheedy's Allison, by far my favorite character, will forever continue to make her dandruff-derived objets and her all-carbs all-the-time sandwiches. Also priceless: Anthony Michael Hall's shambling diffidence, so hard-fought but so hilariously ill-concealed, and Judd Nelson's marvleous line reading of the single word "Claire," turning the name into some sort of insolent question. The Breakfast Club is snappily written, crisply defined, and cleverly art-directed, and in terms of pacing, it couldn't work better. Even the precipitous couplings at the end, some of them real head-scratchers, actually help the movie: we don't leave with any false sense that anything has been fixed or made permanent, and the excitement of making right and wrong choices at the same time is preserved. Pretty in Pink, a much more sober film however poppy it also is, gets a similar boost from what seem like errors. Andie's romantic trajectory just isn't what we expect, and the widely circulated reports of last-minute script changes augment the climactic sense of compromise. But Andie's compromises were always what was most interesting about her, right alongside her winning and utterly believable rapport with her kindly burned-out dad and the limpid, hugely gratifying accessibility of Molly Ringwald across her whole performance. Pretty in Pink starts and ends in imperfection—nicely if unintentionally underlined by the fact that Andie's "do it yourself" prom dress, which occasions her happy ending, is actually, let's be real, quite unflattering. The movie is poignant even when it's funny, funny even when it's angry ("WHAT about PROM, BLANE??!"), and enormously embraceable. It lacks, mercifully, any Long Duck Dong instance of mean and boring stereotype, and in the hands of D.P. Tak Fujimoto—later a godsend to The Silence of the Lambs and The Sixth Sense—the movie doesn't look bad, either. The Psychedelic Furs sound almost as techno-thrilling on the Pink soundtrack as the Simple Minds do on The Breakfast Club's. So riddle me this: why can't these movies get any respect? (Click

The Breakfast Club is snappily written, crisply defined, and cleverly art-directed, and in terms of pacing, it couldn't work better. Even the precipitous couplings at the end, some of them real head-scratchers, actually help the movie: we don't leave with any false sense that anything has been fixed or made permanent, and the excitement of making right and wrong choices at the same time is preserved. Pretty in Pink, a much more sober film however poppy it also is, gets a similar boost from what seem like errors. Andie's romantic trajectory just isn't what we expect, and the widely circulated reports of last-minute script changes augment the climactic sense of compromise. But Andie's compromises were always what was most interesting about her, right alongside her winning and utterly believable rapport with her kindly burned-out dad and the limpid, hugely gratifying accessibility of Molly Ringwald across her whole performance. Pretty in Pink starts and ends in imperfection—nicely if unintentionally underlined by the fact that Andie's "do it yourself" prom dress, which occasions her happy ending, is actually, let's be real, quite unflattering. The movie is poignant even when it's funny, funny even when it's angry ("WHAT about PROM, BLANE??!"), and enormously embraceable. It lacks, mercifully, any Long Duck Dong instance of mean and boring stereotype, and in the hands of D.P. Tak Fujimoto—later a godsend to The Silence of the Lambs and The Sixth Sense—the movie doesn't look bad, either. The Psychedelic Furs sound almost as techno-thrilling on the Pink soundtrack as the Simple Minds do on The Breakfast Club's. So riddle me this: why can't these movies get any respect? (Click