The Oscars. The Emmys. The Tonys. The Obies. The Césars. The Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards. Employee of the Month. National Junior Honor Society. And now: The Fifties.

With the awards-baity fall movie season about to bow, 'tis the season for assessing the goods that have been on offer thus far in the year. Most prognosticators agree that

United 93,

World Trade Center,

The Devil Wears Prada (care of Meryl Streep), and

Half Nelson (care of Ryan Gosling) are the only January-August releases likely to have any impact on the top categories of next year's Oscars. Of course, we've already seen plenty of potential action in places like Animated Feature, Documentary Feature (especially with

An Inconvenient Truth and

Why We Fight), and Visual Effects. Maybe a screenplay nod for

Little Miss Sunshine, too, but that's about it.

Still—and you had to know this was coming—I'm less interested in psyching out the Academy than in looking back at my own favorites from the winter, spring, and summer seasons of 2006. I'm not the first to

hop this train, but now that I've officially seen 50 of this year's stateside releases, it seems like an opportune moment for a progress report. Plus, since no awards slate, real or imaginary, is complete without a

Mrs. Harris controversy, you'll just have to accept the fact that I'm considering that film, which was intended for theatrical distribution but somehow got sold last fall to HBO, as a 2006 release. Grin and bear it. Be happy for Annette.

And with that—we're off!

Best Picture CleanDave Chappelle's Block PartyDrawing Restraint 9Inside ManTristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull StoryRunners-Up: L'Enfant

CleanDave Chappelle's Block PartyDrawing Restraint 9Inside ManTristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull StoryRunners-Up: L'Enfant,

The Descent,

Three TimesI'm still waiting for a real gobsmacker to roll down the pike. For now, Olivier Assayas' patient, subdued, but visually specific melodrama about a recovering drug addict ambivalently re-fitting herself for motherhood stands handily above the rest of the pack.

Best Director

Olivier Assayas,

CleanMichel Gondry,

Dave Chappelle's Block PartySpike Lee,

Inside ManNeil Marshall,

The DescentMichael Winterbottom,

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull StoryRunners-Up: Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne,

L'Enfant; João Pedro Rodrigues,

Two DriftersAgain,

Clean is so carefully and unpretentiously observant, gathering force as it continues without any histrionics, that I can't vote against Assayas. Still, Spike Lee makes a strong bid here, letting loose with an energetic, suspenseful, but deftly comic approach to a sturdy screenplay that needn't have been as witty and memorable as Lee made it. He expands his repertoire considerably, as well as his commercial prospects, but also makes

Inside Man tonally and formally consistent within his body of work.

Best ActressAnnette Bening,

Mrs. Harris

Maggie Cheung,

CleanAna Cristina De Oliveira,

Two DriftersGretchen Mol,

The Notorious Bettie PageKeke Palmer,

Akeelah and the BeeRunners-Up: None

Mol is the whole show in

Bettie Page, fabricating personality, depth, and variation despite a weirdly tentative and direction-less script. Still, Cheung takes the cake with her deft underplaying, the way she listens to fellow actors and visibly reflects on what is happening rather than recycling clichés of zoned-out addiction or listless, weary recovery. Plus, she isn't unaccountably dull, like Cate Blanchett is in

Little Fish.

Best ActorChang Chen,

Three Times

Steve Coogan,

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull StoryJérémie Renier,

L'EnfantDenzel Washington,

Inside ManRay Winstone,

The PropositionRunners-Up: None

The ever-reliable Chang is something of a space-filler here. Renier, Washington, and Winstone rise more than admirably to their occasions, each of them responsible for some truly special moments in their films. Edward Norton (

Down in the Valley) and Aaron Eckhart (

Thank You for Smoking) won admiring reviews, but I found them both too smug by half, too transparent in assembling their performances. I'm clapping most loudly for Coogan, who plays "himself" as an even pettier, funnier, more feather-fluffing hedonist than he did in

Coffee and Cigarettes, but I'll still be surprised (and dismayed) if any of these fellas winds up on my year-end list.

Best Supporting Actress

Seema Biswas,

WaterEmily Blunt,

The Devil Wears PradaCharlotte Rampling,

LemmingMeryl Streep,

A Prairie Home CompanionEmily Watson,

The PropositionRunners-Up: Jeanne Balibar,

Clean; Joan Cusack,

Friends with Money; Edie Falco,

Freedomland; Meryl Streep,

The Devil Wears PradaAmidst the shimmering decorousness and obvious scripting in

Water, Seema Biswas plays the single persuasive human, and she's fascinating. I'm not sure the movie means to be about her by the end, but she's so conflicted and captivating that she carries the whole film everywhere she moves. All of that being said, I'd be nearly as happy recognizing the other terrific nominees. Your whole heart goes out to Watson in

The Proposition, even when she's technically on the side of wrong. Rampling is as deeply unnerving in

Lemming as Emily Blunt is enchanting in her third-tier role in

Prada. As for Streep, she's very funny in

Prada, but the whole movie's being handed to her without quite challenging her, and she has a few more facets and less predictable timing in

Prairie.

Best Supporting ActorRob Brydon,

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull StoryWoody Harrelson,

A Prairie Home CompanionDavid Morse,

Down in the Valley

Nick Nolte,

CleanJérémie Segard,

L'EnfantRunners-Up: Jim Broadbent,

Art School Confidential; Rory Culkin,

Down in the Valley; Robert Downey, Jr.,

A Scanner Darkly; Jason Isaacs,

Friends with Money; Clive Owen,

Inside ManBrydon is a hoot, and also very touching; Harrelson catches the light in his jaunty routines with John C. Reilly; David Morse keeps a stellar balance of the autocratic and the affectionate as Evan Rachel Wood's father in

Down in the Valley, worried into bullishness. Still, Nolte's restraint and honest sentimentality as a grieving father in

Clean, befriending his unreliable daughter-in-law against the wishes of his dying wife, make the very, very most of a trickily written role.

ScreenplayClean, Olivier Assayas

Inside Man, Russell Gewirtz

Mrs. Harris, Phyllis Nagy

A Scanner Darkly, Richard Linklater

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story, Frank Cottrell Boyce

Runner-Up: Lemming, Dominik Moll and Gilles Marchand

The writing has been the most consistently inconsistent element in most of the good movies I've seen this year; there haven't even been enough strong showings to warrant separate races for Original and Adaptation. If

Clean and

Inside Man weren't so well directed, the scripts might not seem very special. By contrast,

Mrs. Harris and

A Scanner Darkly are more arresting as pieces of writing than the interesting but not particularly urgent films manage to let on.

Tristram Shandy is the cleverest by far, both at rhyming so well with the source novel's entropic ribaldry and at finding jokes as well as honest emotion inside so many corners of the filmmaking process.

Best CinematographyClean, Eric Gautier

The Descent, Sam McCurdy

L'Enfant

L'Enfant, Alain Marcoen

The Road to Guantánamo, Marcel Zyskind

Three Times, Mark Ping-bin Lee

Runners-Up: Dave Chappelle's Block Party, Ellen Kuras;

The Hills Have Eyes, Maxime Alexandre;

Poseidon, John Seale

All five of these films make superb choices about what to shoot, and though only

Three Times is self-consciously beautiful, they all furnish their viewers with intensely hypnotic visual experiences.

L'Enfant narrowly surpasses

Clean in its precise choreography of camera movements, and in the subtle, seemingly on-the-fly framings that nonetheless impart to the proceedings, as does Gautier's work in

Clean, an almost novelistic wealth of detail.

Best Film EditingClean, Luc Barnier

Dave Chappelle's Block Party

Dave Chappelle's Block Party, Jeff Buchanan, Sarah Flack, and Jamie Kirkpatrick

Inside Man, Barry Alexander Brown

Police Beat, Joe Shapiro and Mark Winitsky

United 93, Clare Douglas, Richard Pearson, and Christopher Rouse

Runners-Up: Brick, Rian Johnson;

The Descent, Jon Harris;

Mission: Impossible III, Maryann Brandon and Mary Jo Markey;

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story, Peter Christelis

A race that would hold up just as well at year's end, though only

United 93 stands any chance at being so recognized. Among distinguished company,

Dave Chappelle's Block Party not only finds the buried jewels in what I expect were mounds of footage, but each embedded performance has a distinctive shape and cadence, and the whole film follows a lovely arc from straightforward concert doc to a more resonant urban collage.

Best Art DirectionArt School Confidential, Howard Cummings

The Descent, Simon Bowles

Monster House

Monster House, Ed Verreaux

Poseidon, William Sandell

Three Times, Huang Wen-ying

Runners-Up: Drawing Restraint 9, Matthew D. Ryle and Matthew Barney;

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story, John Paul Kelly

It started the summer as the bête noire among blockbusters, but I found

Poseidon to be a craftily made and mounted picture, nowhere more so than in its pristine design by Sandell, who knows his way around watery wreckage (see

The Perfect Storm and

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World). The ornate gorgeousness of

Three Times also begs to be considered, but in the end, the deliciously macabre

Monster House is my favorite, getting everything right from the omnivorous house of the title to the three appealingly drawn protagonists to the laugh-out-loud graphics of an arcade game called "Thou Art Dead."

Best Costume DesignThe Devil Wears Prada, Patricia Field

Drawing Restraint 9

Drawing Restraint 9, Matthew Barney

Friends with Money, Michael Wilkinson

Little Miss Sunshine, Nancy Steiner

The Notorious Bettie Page, John A. Dunn

Runners-Up: Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, Penny Rose;

A Prairie Home Companion, Catherine Marie Thomas;

The Proposition, Margot Wilson

I'm tempted to place the star next to

Prada's colorful and off-the-wall ensembles, which parody couture without being contemptuous of it, or else next to the aptly chosen daywear of

Friends with Money, so attuned to how the abashedly rich keep dressing down as normal folks, while Jennifer Aniston's Olivia keeps popping up in duds that her gal-pals have probably bought for her. Still, there's no getting around the rococo parade outfits, the scrumptious textures, and the wild, weird meditations on Japanese culture that Matthew Barney built into his almost sculptural clothes for

Drawing Restraint 9.

Best SoundDave Chappelle's Block PartyInside Man Miami ViceMission: Impossible IIIUnited 93Runners-Up: Clean

Miami ViceMission: Impossible IIIUnited 93Runners-Up: Clean;

The Hills Have Eyes;

A Prairie Home Companion;

TsotsiMiami Vice may get an awful lot of things wrong, but the sound design isn't one of them. Note the expertly chosen and smartly incorporated songs, a score by John Murphy that detours away from the more obvious residues of the TV show, and some truly horrifying foley work for the shoot-outs and trailer-park explosions. The overlaid dialogue and sound elements of

United 93 are nearly as crucial to the effectiveness of that film, and

Block Party is one of the better-sounding concert docs, without losing its necessarily ragged edge. Already a sterling field, then... hopefully with still more glories to come between now and New Year's Eve!

Meanwhile, my Dishonor Roll of 2006 so far would run like this:

Worst Picture: Ask the DustWorst Director: Michael Caton-Jones,

Basic Instinct 2Worst Actress: Natalie Portman,

V for VendettaWorst Actor: Kevin Kline,

A Prairie Home CompanionWorst Supporting Actress: Idina Menzel,

Ask the DustWorst Supporting Actor: Simon Baker,

The Devil Wears PradaWorst Screenplay: Lady in the Water, M. Night Shyamalan

Worst Cinematography: Thank You for Smoking, James Whitaker

Worst Film Editing: Why We Fight, Nancy Kennedy

Labels: Best 2006, Fifties

StinkyLulu's monthly feature Supporting Actress Smackdown fully earns its name today, as the usually simpatico participants file notably divergent opinions on almost all of the performances. True, no one waves a flag for Thelma Ritter's sixth winless nomination, for Birdman of Alcatraz, but she's very much the exception that proves the rule. Oscar's own anointee, Patty Duke in The Miracle Worker, snags an easy echoing vote from me. Neither StinkyLulu nor Tim nor Nathaniel casts any aspersion on the performance, but sadly, Mrs. Iselin's voracious brainwashing campaign has rolled onward, unfettered, and claimed all of my comrades! Or, while we're grabbing at crass and obvious metaphors, am I simply blind and deaf to Angela Lansbury's brilliance in The Manchurian Candidate? (Her inspired scene work, I appreciate; her irreproachable proficiency, I get; but I see no brilliance, hear no brilliance.) Read all about it here, though your tour isn't complete this month until you've also taken in Canadian Ken's vivid, funny, and beautifully argued impressions of all five performances.

StinkyLulu's monthly feature Supporting Actress Smackdown fully earns its name today, as the usually simpatico participants file notably divergent opinions on almost all of the performances. True, no one waves a flag for Thelma Ritter's sixth winless nomination, for Birdman of Alcatraz, but she's very much the exception that proves the rule. Oscar's own anointee, Patty Duke in The Miracle Worker, snags an easy echoing vote from me. Neither StinkyLulu nor Tim nor Nathaniel casts any aspersion on the performance, but sadly, Mrs. Iselin's voracious brainwashing campaign has rolled onward, unfettered, and claimed all of my comrades! Or, while we're grabbing at crass and obvious metaphors, am I simply blind and deaf to Angela Lansbury's brilliance in The Manchurian Candidate? (Her inspired scene work, I appreciate; her irreproachable proficiency, I get; but I see no brilliance, hear no brilliance.) Read all about it here, though your tour isn't complete this month until you've also taken in Canadian Ken's vivid, funny, and beautifully argued impressions of all five performances. Unfortunately, one turn you won't hear us dissect is Jane Fonda's in the redolent, subversive, and nearly extraordinary 1962 drama Walk on the Wild Side. In only her second or third movie role, Jane Fonda plays Kitty Twist (!), a hot-tempered hot patootie whom Manchurian idol Laurence Harvey meets on the side of a dusty Texas highway. They're both hitching to New Orleans—he in order to reclaim a lover who's gotten away, she in order to hit, gobble, and fucking own the whole town. If Fonda's acting serves any indication, usurping the screen as her own birthright and eminent domain, we should all be placing our bets on Kitty.

Unfortunately, one turn you won't hear us dissect is Jane Fonda's in the redolent, subversive, and nearly extraordinary 1962 drama Walk on the Wild Side. In only her second or third movie role, Jane Fonda plays Kitty Twist (!), a hot-tempered hot patootie whom Manchurian idol Laurence Harvey meets on the side of a dusty Texas highway. They're both hitching to New Orleans—he in order to reclaim a lover who's gotten away, she in order to hit, gobble, and fucking own the whole town. If Fonda's acting serves any indication, usurping the screen as her own birthright and eminent domain, we should all be placing our bets on Kitty. Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

Nick's Flick Picks: The Blog

The blogosphere sheds a collective tear today as one of its most perfect objects reaches sublime completion... which is another way of saying, in as many mixed metaphors as possible, that

The blogosphere sheds a collective tear today as one of its most perfect objects reaches sublime completion... which is another way of saying, in as many mixed metaphors as possible, that  With out-of-town company to entertain and end-of-summer errands to run, this blog has got little to show for itself today—nothing, for sure, that's remotely on the level of

With out-of-town company to entertain and end-of-summer errands to run, this blog has got little to show for itself today—nothing, for sure, that's remotely on the level of  Speaking of nineteenth-century France (!), the latest full review on

Speaking of nineteenth-century France (!), the latest full review on

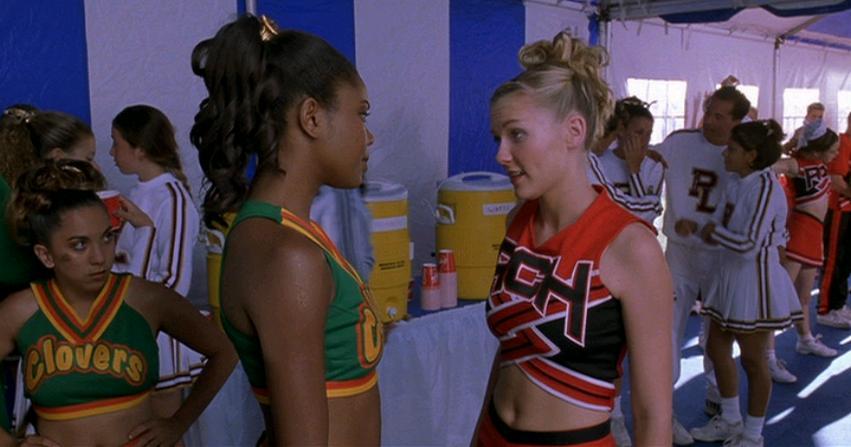

I haven't met anyone who thinks Bring It On is a bad film, though I can only assume such characters exist. Rather, in my experience, Bring It On cleaves its viewership into two camps: those who see a merely adequate but derivative and utterly unspecial movie about cheerleading forchrissakes, and those who see the Grand Illusion of modern high-school comedies. I have found that it is difficult to communicate across the divide between the agnostics and the devotés. It's even a little bit difficult to communicate among the devotés, because for the converted, to be in the presence of Bring It On is to be bathed in total, self-evident pleasure. Explanation falters out of what amounts to unnecessity, but let's try. Let's start with the single frame I have reproduced here, from a mutedly climactic scene where duelling squad captains Torrance (Kirsten Dunst) and Isis (Gabrielle Union) exchange succinct, slightly tense, but generous advice about how to keep their cheerleaders in perfect formation during their respective routines at the national competition. Note that almost every primary color as yet discovered by man is evidenced in this shot, but the overall effect is more engaging than garish. Note that the strong, diagonal, and yet flattering designs for the uniforms of the Rancho Carne Toros and the Compton Clovers toe a precocious line between a silly, unexploitative sauciness and a tough, sporting conviction about the tasks at hand. Note that the framing plays up a symmetry between Torrance and Isis, conveying that these longtime rivals have entered into something like a mutual understanding, even as the sharp contrast between the two backgrounds—blue and white color bars behind Isis, a percolating crowd behind Torrance—continue to set them off from each other. Actually, I emend myself: Torrance is the Prime Meridian of this shot, exactly dividing the two background fields on either side of her, subtly reminding us that the scene isn't so much about a standoff between the mavens as a turning point within Torrance herself, who now meets Isis as a fond equal without relinquishing any of her own competitive zeal. Chicas, you can pause or replay Bring It On liberally and find care, undertones, and tiny formal ironies like these. It isn't Orson Welles, but for crying out loud, when was the last time color, composition, blocking, and design were this precisely calibrated in a teen comedy?

I haven't met anyone who thinks Bring It On is a bad film, though I can only assume such characters exist. Rather, in my experience, Bring It On cleaves its viewership into two camps: those who see a merely adequate but derivative and utterly unspecial movie about cheerleading forchrissakes, and those who see the Grand Illusion of modern high-school comedies. I have found that it is difficult to communicate across the divide between the agnostics and the devotés. It's even a little bit difficult to communicate among the devotés, because for the converted, to be in the presence of Bring It On is to be bathed in total, self-evident pleasure. Explanation falters out of what amounts to unnecessity, but let's try. Let's start with the single frame I have reproduced here, from a mutedly climactic scene where duelling squad captains Torrance (Kirsten Dunst) and Isis (Gabrielle Union) exchange succinct, slightly tense, but generous advice about how to keep their cheerleaders in perfect formation during their respective routines at the national competition. Note that almost every primary color as yet discovered by man is evidenced in this shot, but the overall effect is more engaging than garish. Note that the strong, diagonal, and yet flattering designs for the uniforms of the Rancho Carne Toros and the Compton Clovers toe a precocious line between a silly, unexploitative sauciness and a tough, sporting conviction about the tasks at hand. Note that the framing plays up a symmetry between Torrance and Isis, conveying that these longtime rivals have entered into something like a mutual understanding, even as the sharp contrast between the two backgrounds—blue and white color bars behind Isis, a percolating crowd behind Torrance—continue to set them off from each other. Actually, I emend myself: Torrance is the Prime Meridian of this shot, exactly dividing the two background fields on either side of her, subtly reminding us that the scene isn't so much about a standoff between the mavens as a turning point within Torrance herself, who now meets Isis as a fond equal without relinquishing any of her own competitive zeal. Chicas, you can pause or replay Bring It On liberally and find care, undertones, and tiny formal ironies like these. It isn't Orson Welles, but for crying out loud, when was the last time color, composition, blocking, and design were this precisely calibrated in a teen comedy? Jackie Brown starts hitting pitch-perfect notes in the opening credits, and it literally never stops. Pam Grier, dolled up for her job as a stewardess for Cabo Air, glides into the right edge of the frame, while Bobby Womack's creamily desperate anthem "Across 110th Street" sets a pristine, hummable stage for both the character and the movie. It's such a simple gesture, capturing Jackie so quickly at her coolest, then gradually hastening her toward the airport gate as she realizes she's running out of time. The whole movie will plot this same course, not just because Jackie stays all but invisible for the next half-hour (and therefore has to hustle a little to reclaim her own film), but because Tarantino's direction and his script are so exquisitely keyed in to Jackie's pragmatism and her panic: "I make about sixteen thousand, with retirement benefits that ain't worth a damn... If I lose my job, I gotta start all over again, but I got nothing to start over with." Jackie's basic, wholly adequate motivation for lawlessness is that from where she's standing, she can see the dying of the light. When she drags herself out of jail, she worries about how bad she looks. When she sits down with her obviously smitten bail bondsman, the first thing they discuss is how to quit smoking without gaining weight. Pam Grier is so pert, charismatic, and funny in the role that there isn't anything cloying about Jackie's anxieties, just as there is nothing overly precious about the film's presentation of them—even when Tarantino lays down a vocal track of a much younger Grier singing "Long Time Woman" as a funky and succinct counterpoint to this older, soberer, but still very funky version of herself. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Jackie Brown is how unfoolish and—a very un-Tarantino word—how wise this film looks and sounds while espousing a then-34-year-old, nonblack, male filmmaker's vision of Jackie's predicament. Though the colors and songs are all Tarantino-brite, the framings are contemplative and often very simple, even amidst key episodes in the criss-crossy plot; as the narrative accelerates and the vise of possible failure closes around Jackie and her weathered but plucky accomplice Max Cherry (an invaluable Robert Forster), the film never deviates from its carefully restrained pace and rhythms. Almost every sequence is designed such that seemingly simple actions communicate several things at once: Jackie trying on a new suit, Bridget Fonda refusing to answer a phone, Robert De Niro looking for his car in a parking lot, Lisa Gay Hamilton making nervous contact with Jackie in a food court. Every one of them is crucial to Jackie Brown's plot, but they've all been filmed with the frisky, on-the-fly texture of grace notes and improvs. The film has an exacting, exquisitely calibrated structure, loping forward and then looping backward, but the steady hand and living, breathing humanity behind every moment lend Jackie Brown a warm, plausible, and deeply enjoyable spontaneity.

Jackie Brown starts hitting pitch-perfect notes in the opening credits, and it literally never stops. Pam Grier, dolled up for her job as a stewardess for Cabo Air, glides into the right edge of the frame, while Bobby Womack's creamily desperate anthem "Across 110th Street" sets a pristine, hummable stage for both the character and the movie. It's such a simple gesture, capturing Jackie so quickly at her coolest, then gradually hastening her toward the airport gate as she realizes she's running out of time. The whole movie will plot this same course, not just because Jackie stays all but invisible for the next half-hour (and therefore has to hustle a little to reclaim her own film), but because Tarantino's direction and his script are so exquisitely keyed in to Jackie's pragmatism and her panic: "I make about sixteen thousand, with retirement benefits that ain't worth a damn... If I lose my job, I gotta start all over again, but I got nothing to start over with." Jackie's basic, wholly adequate motivation for lawlessness is that from where she's standing, she can see the dying of the light. When she drags herself out of jail, she worries about how bad she looks. When she sits down with her obviously smitten bail bondsman, the first thing they discuss is how to quit smoking without gaining weight. Pam Grier is so pert, charismatic, and funny in the role that there isn't anything cloying about Jackie's anxieties, just as there is nothing overly precious about the film's presentation of them—even when Tarantino lays down a vocal track of a much younger Grier singing "Long Time Woman" as a funky and succinct counterpoint to this older, soberer, but still very funky version of herself. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Jackie Brown is how unfoolish and—a very un-Tarantino word—how wise this film looks and sounds while espousing a then-34-year-old, nonblack, male filmmaker's vision of Jackie's predicament. Though the colors and songs are all Tarantino-brite, the framings are contemplative and often very simple, even amidst key episodes in the criss-crossy plot; as the narrative accelerates and the vise of possible failure closes around Jackie and her weathered but plucky accomplice Max Cherry (an invaluable Robert Forster), the film never deviates from its carefully restrained pace and rhythms. Almost every sequence is designed such that seemingly simple actions communicate several things at once: Jackie trying on a new suit, Bridget Fonda refusing to answer a phone, Robert De Niro looking for his car in a parking lot, Lisa Gay Hamilton making nervous contact with Jackie in a food court. Every one of them is crucial to Jackie Brown's plot, but they've all been filmed with the frisky, on-the-fly texture of grace notes and improvs. The film has an exacting, exquisitely calibrated structure, loping forward and then looping backward, but the steady hand and living, breathing humanity behind every moment lend Jackie Brown a warm, plausible, and deeply enjoyable spontaneity. Cast here as a youngish Eleanor Roosevelt, Garson starts her performance on some bizarre and off-putting notes, quite literally: her version of Eleanor's fluty, fruity Old New York accent may well be expert mimicry, but like Jennifer Jason Leigh's take on Dorothy Parker, it's too mannered and outlandish to work as drama. It doesn't help that the script wheedles her for a Big Crying Scene (though Garson's unflamboyant build-up almost makes it work) or that it can't quite decide whether to canonize Eleanor or domesticate her (if you'll believe it, Eleanor sits for the climactic scene while FDR stands). The translucent likeability that anchors Garson's best work can't shine through in this fusty project, but she's still the most watchable actor on-screen, and she mines some persuasively intimate and character-revealing moments, as when she settles down silently in a chair and exchanges a silent, articulate smile with her newly afflicted husband.

Cast here as a youngish Eleanor Roosevelt, Garson starts her performance on some bizarre and off-putting notes, quite literally: her version of Eleanor's fluty, fruity Old New York accent may well be expert mimicry, but like Jennifer Jason Leigh's take on Dorothy Parker, it's too mannered and outlandish to work as drama. It doesn't help that the script wheedles her for a Big Crying Scene (though Garson's unflamboyant build-up almost makes it work) or that it can't quite decide whether to canonize Eleanor or domesticate her (if you'll believe it, Eleanor sits for the climactic scene while FDR stands). The translucent likeability that anchors Garson's best work can't shine through in this fusty project, but she's still the most watchable actor on-screen, and she mines some persuasively intimate and character-revealing moments, as when she settles down silently in a chair and exchanges a silent, articulate smile with her newly afflicted husband. The film and the performance get off to a worrisome start: as former hooker Loren wanes on her deathbed, her heart of gold at last giving out, aging playboy and longtime client Marcello Mastroianni ponders all the times he promised his love but ignored her pleas for marriage and respectability. Loren is timelessly fetching as she strides down a Neapolitan street in the film's most famous shot; still, it's all a little tawdry and clichéd, like Malèna played for casual laughs. Everything brightens considerably, though, when Loren "miraculously" revives, revealing her own duplicitous agendas, and she elevates the movie's second half into a tasty, energetic, and admirably humane comedy. She's sexy, clever, and funny, as three-dimensional in her personality as in her formidable physique. Loren won an Oscar three years previously for the sturm and drang of De Sica's Two Women, but here she shows more art and more charm—call her Irene Dunne Italian Style.

The film and the performance get off to a worrisome start: as former hooker Loren wanes on her deathbed, her heart of gold at last giving out, aging playboy and longtime client Marcello Mastroianni ponders all the times he promised his love but ignored her pleas for marriage and respectability. Loren is timelessly fetching as she strides down a Neapolitan street in the film's most famous shot; still, it's all a little tawdry and clichéd, like Malèna played for casual laughs. Everything brightens considerably, though, when Loren "miraculously" revives, revealing her own duplicitous agendas, and she elevates the movie's second half into a tasty, energetic, and admirably humane comedy. She's sexy, clever, and funny, as three-dimensional in her personality as in her formidable physique. Loren won an Oscar three years previously for the sturm and drang of De Sica's Two Women, but here she shows more art and more charm—call her Irene Dunne Italian Style. To respond to the two most common talking-points around this Oscared performance: yes, I think Anna Held is a crucial enough role with enough screen time to count as a leading performance, but no, I don't think that her famous, last-act telephone call to the Great Ziegfeld himself—congratulating him on his second marriage while bursting into tears of regret—is really all that special. Throughout, Rainer ratchets up the antic stage business and vocal affectations, landing somewhere between overripe comedy and overly emphatic imitation of the real Anna Held (who, to be fair, apparently did cut a fluttery, slightly outlandish figure). Ultimately, Rainer's approach kept me on the surface of the character instead of drawing me into her thoughts and feelings; the exception that proved the rule was her calmest scene, an encounter with Ziegfeld's lovely, young, and boozy new mistress, where Rainer underplays her moment of realization, her sorrow, her jealousy, and her frank pity for the latest fling who thinks she's a keeper.

To respond to the two most common talking-points around this Oscared performance: yes, I think Anna Held is a crucial enough role with enough screen time to count as a leading performance, but no, I don't think that her famous, last-act telephone call to the Great Ziegfeld himself—congratulating him on his second marriage while bursting into tears of regret—is really all that special. Throughout, Rainer ratchets up the antic stage business and vocal affectations, landing somewhere between overripe comedy and overly emphatic imitation of the real Anna Held (who, to be fair, apparently did cut a fluttery, slightly outlandish figure). Ultimately, Rainer's approach kept me on the surface of the character instead of drawing me into her thoughts and feelings; the exception that proved the rule was her calmest scene, an encounter with Ziegfeld's lovely, young, and boozy new mistress, where Rainer underplays her moment of realization, her sorrow, her jealousy, and her frank pity for the latest fling who thinks she's a keeper.

—and click over to StinkyLulu's

—and click over to StinkyLulu's  Just in time for my departure from the East Coast, the

Just in time for my departure from the East Coast, the  The Oscars. The Emmys. The Tonys. The Obies. The Césars. The Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards. Employee of the Month. National Junior Honor Society. And now: The Fifties.

The Oscars. The Emmys. The Tonys. The Obies. The Césars. The Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards. Employee of the Month. National Junior Honor Society. And now: The Fifties. Clean

Clean Enjoy your day. Blow out all your candles. Here's to 46 more years of genius... speaking of which, I'll look forward to seeing you and Jude and Kate and Patricia

Enjoy your day. Blow out all your candles. Here's to 46 more years of genius... speaking of which, I'll look forward to seeing you and Jude and Kate and Patricia  It's a bird! It's a plane! It's a magazine ad for Ray-Ban sunglasses, featuring Tyrese and Josh Wald! (Mmmmm...

It's a bird! It's a plane! It's a magazine ad for Ray-Ban sunglasses, featuring Tyrese and Josh Wald! (Mmmmm...  It's not every day that I revisit a movie I disliked as strongly as I did

It's not every day that I revisit a movie I disliked as strongly as I did  So far, at least on my watch, the British horror import

So far, at least on my watch, the British horror import  As I keep marching forward through Oscar nominees of the past, I am occasionally regretting that I splurged so early on so much good stuff and left a steaming pile of Greatest Show on Earths and Great Santinis to contend with in my future. "Great," needless to say, is a false promise in both instances. I'm also wading through a lot of interesting mediocrities like

As I keep marching forward through Oscar nominees of the past, I am occasionally regretting that I splurged so early on so much good stuff and left a steaming pile of Greatest Show on Earths and Great Santinis to contend with in my future. "Great," needless to say, is a false promise in both instances. I'm also wading through a lot of interesting mediocrities like  And so Kiss of the Spider Woman, a film in which I had recognized glimmers of myself with such early and total astonishment, stunned me just as much by calling out my naïvetés and myopias—not from some new or rejected frontier of knowledge, where I was used to being shocked or upbraided by life, but from an already treasured and intimate object. It's no mystery to me how Babenco's film sets this sort of trap, at least for a certain kind of viewer. Where the early sequences are lusciously cinephiliac, with their mocking but affectionate recreations of dubious melodramas, and their willowy transitions from that universe of screen memory to the clammy, witty, and exciting reality of the jail cell, the later sequences assert their politics more forthrightly, with the hard lighting, strained faces, and tightened editing of other Latin American political dramas, like Luis Puenzo's The Official Story or Babenco's own magnificent Pixote. Fans who take Molina's epicurean escapism at nearly face value, as I did, are likely to feel like the second hour sells them out. The seductions of John Neschling's music or Patricio Bisso's versatile costuming don't evaporate as the film reaches its grave climax, but they shape-shift in a way that requires a full immersion in every side of what Babenco, working from Puig's ingenious template, has constructed up to that point. Almost by definition, the movie divides its sympathetic audience of marginalized liberals, forcing them to recombine by movie's end in a richer, more expansive spirit of solidarity: quite literally, and purposefully, less fabulous than the earlier chapters. It's a hugely ambitious journey that the movie takes, with impressive if erratic artistry. Nothing in the movie, not the acting or the editing or the camerawork or the story structure, is immune to miscalculation here or there, but Kiss also achieves substantial, flavorful successes in each of these areas. Best of all, because it is subtle and intelligent in raising questions about storytelling, spectatorship, sympathy, borderzones, clichés, stereotypes, and sexual politics—terrains where a great many movies start bonking you over the head, or else just flee in all the wrong directions—Kiss of the Spider Woman consistently surpasses its own flaws, challenges your own sureties, turning them all into productive questions rather than simple blemishes.

And so Kiss of the Spider Woman, a film in which I had recognized glimmers of myself with such early and total astonishment, stunned me just as much by calling out my naïvetés and myopias—not from some new or rejected frontier of knowledge, where I was used to being shocked or upbraided by life, but from an already treasured and intimate object. It's no mystery to me how Babenco's film sets this sort of trap, at least for a certain kind of viewer. Where the early sequences are lusciously cinephiliac, with their mocking but affectionate recreations of dubious melodramas, and their willowy transitions from that universe of screen memory to the clammy, witty, and exciting reality of the jail cell, the later sequences assert their politics more forthrightly, with the hard lighting, strained faces, and tightened editing of other Latin American political dramas, like Luis Puenzo's The Official Story or Babenco's own magnificent Pixote. Fans who take Molina's epicurean escapism at nearly face value, as I did, are likely to feel like the second hour sells them out. The seductions of John Neschling's music or Patricio Bisso's versatile costuming don't evaporate as the film reaches its grave climax, but they shape-shift in a way that requires a full immersion in every side of what Babenco, working from Puig's ingenious template, has constructed up to that point. Almost by definition, the movie divides its sympathetic audience of marginalized liberals, forcing them to recombine by movie's end in a richer, more expansive spirit of solidarity: quite literally, and purposefully, less fabulous than the earlier chapters. It's a hugely ambitious journey that the movie takes, with impressive if erratic artistry. Nothing in the movie, not the acting or the editing or the camerawork or the story structure, is immune to miscalculation here or there, but Kiss also achieves substantial, flavorful successes in each of these areas. Best of all, because it is subtle and intelligent in raising questions about storytelling, spectatorship, sympathy, borderzones, clichés, stereotypes, and sexual politics—terrains where a great many movies start bonking you over the head, or else just flee in all the wrong directions—Kiss of the Spider Woman consistently surpasses its own flaws, challenges your own sureties, turning them all into productive questions rather than simple blemishes. Having heard from a little birdie that

Having heard from a little birdie that  This kind of haughty, anti-intellectual approach is most thrillingly avoided in the tantalizing and fact-soaked film The Corporation, an emblem of leftist cinema at its most honest and effective. Indeed, The Corporation does a magisterial job of raising all sorts of urgent alarms about the traumatic effects of modern capitalism, without privileging reductive cant over concise, illustrated argumentation, and without preaching only to the pre-converted. The premise of the film's opening sequences is sublimely simple, but unexpectedly imposing: that is, to define what a corporation is, exactly—one professor at the Harvard Business School abashedly realizes that nobody has ever quite put this query to him before—and then to sketch the conceptual contours and legal entitlements that don't just allow but require corporations to maximize profits without any ethical qualms or qualifications. From here, the movie hurtles into its second conceit, aligning the hard-wired behaviors of corporations with the basic symptoms of diagnosed psychopaths, and then through a roulette wheel of eloquent case histories. Many of these, like the extended pièce de résistance about how FoxNews quashed their own story about America's contaminated milk supply, achieve the expected goal of arraigning white-collar pirates and amoral dollar-chasers, but the detail and power in the arguments are more supple and lifelike than one usually finds in films of this type. Plus, the pirates often furnish their own swords on which to fall. Wall Street trader Carlton Brown admits that he and every other trader he knows spent September 11, 2001, gleefully selling gold to the highest bidders and relishing the market's good fortune, quite literally. Lucy Hughes, a chirpy vice-president from Initiative Media, tips her hand about how she abets toy manufacturers and other clients to brainwash children into demanding their products. "Is it ethical? I don't know," Lucy admits, but it's the job she has to do, and she does it well. Chris Komisarjevsky, a corporate spin doctor whom some Orwellian neologist has rechristened a "perception manager," describes his job as though the corporations themselves—rather than, say, impoverished laborers or lampooned environmentalists or snookered consumers or corraled protesters or, in one especially vile anecdote, Bolivian citizens who were taxed by Bechtel for the privilege of drinking their own river and rain water—were the victims of an enormously sentimentalized marginality. "I help corporations have a voice," Komisarjevsky testifies, "and I help corporations share their point of view about how they feel about things." Though we almost never hear the interviewers' prompts, it takes a seasoned and careful approach to draw out motivations and rationalizations from such a broad spectrum of CEOs, activists, traders, historians, professors, consultants, and spies. Furthermore, these accounts always refine our sense of how capitalism operates, from its skyscraper summits through its middle management to its immiserated workers: the full canvas of the movie is richer and more important than the local shocks, cheers, or hisses occasioned by any given detail.

This kind of haughty, anti-intellectual approach is most thrillingly avoided in the tantalizing and fact-soaked film The Corporation, an emblem of leftist cinema at its most honest and effective. Indeed, The Corporation does a magisterial job of raising all sorts of urgent alarms about the traumatic effects of modern capitalism, without privileging reductive cant over concise, illustrated argumentation, and without preaching only to the pre-converted. The premise of the film's opening sequences is sublimely simple, but unexpectedly imposing: that is, to define what a corporation is, exactly—one professor at the Harvard Business School abashedly realizes that nobody has ever quite put this query to him before—and then to sketch the conceptual contours and legal entitlements that don't just allow but require corporations to maximize profits without any ethical qualms or qualifications. From here, the movie hurtles into its second conceit, aligning the hard-wired behaviors of corporations with the basic symptoms of diagnosed psychopaths, and then through a roulette wheel of eloquent case histories. Many of these, like the extended pièce de résistance about how FoxNews quashed their own story about America's contaminated milk supply, achieve the expected goal of arraigning white-collar pirates and amoral dollar-chasers, but the detail and power in the arguments are more supple and lifelike than one usually finds in films of this type. Plus, the pirates often furnish their own swords on which to fall. Wall Street trader Carlton Brown admits that he and every other trader he knows spent September 11, 2001, gleefully selling gold to the highest bidders and relishing the market's good fortune, quite literally. Lucy Hughes, a chirpy vice-president from Initiative Media, tips her hand about how she abets toy manufacturers and other clients to brainwash children into demanding their products. "Is it ethical? I don't know," Lucy admits, but it's the job she has to do, and she does it well. Chris Komisarjevsky, a corporate spin doctor whom some Orwellian neologist has rechristened a "perception manager," describes his job as though the corporations themselves—rather than, say, impoverished laborers or lampooned environmentalists or snookered consumers or corraled protesters or, in one especially vile anecdote, Bolivian citizens who were taxed by Bechtel for the privilege of drinking their own river and rain water—were the victims of an enormously sentimentalized marginality. "I help corporations have a voice," Komisarjevsky testifies, "and I help corporations share their point of view about how they feel about things." Though we almost never hear the interviewers' prompts, it takes a seasoned and careful approach to draw out motivations and rationalizations from such a broad spectrum of CEOs, activists, traders, historians, professors, consultants, and spies. Furthermore, these accounts always refine our sense of how capitalism operates, from its skyscraper summits through its middle management to its immiserated workers: the full canvas of the movie is richer and more important than the local shocks, cheers, or hisses occasioned by any given detail.